We were a mystery family, when I was a kid. Indeed, we were a Mystery! family; Sunday afternoons in our household involved delving into Sherlock Holmes, Tommy and Tuppence, Lord Peter Wimsey, and so forth, all introduced to us by Vincent Price initially, because I am An Old. And, yes, we read books, too; I got into Sue Grafton in high school, and even before then I read books about Cam Jansen, Alvin Fernald, and of course the interminable Encyclopedia Brown. I adore the obscure McGurk books. However, the greatest of the fictional detectives for kids, Nancy Drew, was more my older sister’s jam than mine. Though I did read the cookbook as a child and buy it as an adult, of course.

Nancy’s story starts with Edward Stratemeyer. As a youth, he’d idolized Horatio Alger; as an adult, he actually worked with him. Eventually, he created the highly successful Rover Boys, apparently the only series he wrote all the books in. In 1905, he created a syndicate, wherein he hired authors to write novels based on his concepts. In 1926, he had the idea for the Hardy Boys, with the first books’ coming out in 1927. It quickly became apparent that girls were reading the books, too, and Stratemeyer does not seem to have been a man to sleep on a money-making idea. He suggested a character named Stella Strong, to be “What If Hardy Boys But A Single Girl.” Other name options were Diana Drew, Diana Dare, Nan Nelson, Nan Drew, or Helen Hale.

Nancy Drew, as she was eventually known, was officially created by Carolyn Keene. (Here I’d like to shame the Library of Congress for going along with the idea that the true authors’ names should be concealed.) Initially, writing a Nancy Drew paid $125, or over $2000 today. (Or roughly 36 times what I get monthly on Patreon and well over $2000 what I get on Ko-fi in the average month!) The amount dropped to $100 and then $75 during the Depression. Naturally, the Syndicate got all the royalties, not the author.

As for the character herself, in the original books, Nancy was a sixteen-year-old high school graduate, daughter of Carson Drew, a successful lawyer. Her mother had died when she was ten, and Nancy ran the house alongside Hannah Gruen, the housekeeper. Her best friend was Helen Corning. She drove a blue roadster and her boyfriend was Ned Nickerson. She was blonde and blue-eyed.

Well you may ask. It’s not true that all of those traits changed, but within five books, the first of them did. Helen was replaced, with no explanation, with cousins George Fayne and Bess Marvin. Readers will remember George as a tomboy and Bess as a glutton. Nancy’s hair became titian. She was now three when her mother died. The car, in the ‘50s, would become a convertible. In the most recent books, she would even break up with Ned! Which is fine with me, honestly, as I never found Ned interesting enough to be bothered with.

Nancy, it’s true, lives in a fairly white, affluent world for the most part. And the solution to the racism of some of the earlier books was obvious—whitewashing. It’s exactly what you’d expect from a book series first published in 1930. Revivals of the series have attempted to deal with that; recent ones even diversify the cast and work hard to give Bess a personality beyond “she likes to eat.” Nancy Drew and the Clue Crew makes the characters children and gives Bess ability with computers. She still likes to eat, but that’s not all there is to her.

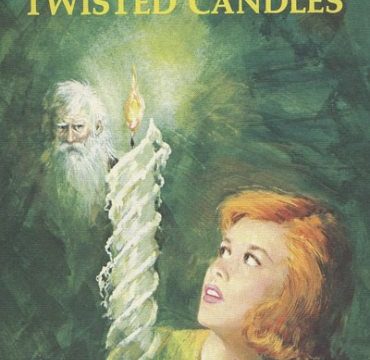

I am not the first person to note the contradictions inherent in Nancy Drew. The only one I read as a child—which I read repeatedly and snatched up when I found it in a Little Free Library at the kids’ school—was The Sign of the Twisted Candles. It’s a fun, involved little story, but it’s also disheartening inasmuch as the heiress in it isn’t given her place just because she’s kind to a man who is being mistreated. I won’t reveal the exact details, because spoilers, but let’s just say that everything is as it should be in the world.

There have been multiple attempts to make a successful movie or TV series about the books, and none of them have quite captured what people want from the character. Many of them were created by men who don’t seem to care about girls’ interests. Others wanted to put an Edgy Twist on it—it’s not surprising that the Riverdale people have taken on Nancy. Often, she moves from the Big City to a small town. There’s one where an adult New York police detective Nancy is solving the murder of, sigh, Bess. That one didn’t make it out of pilot. Another feels like it’s going for what the ‘90s did for/to The Brady Bunch.

The issue, I think, is that Nancy is aspirational, and what you like about her is there even if it’s also kind of contradicted by something else. That’s a hard balance to strike, and the only way to do it is to fully accept it. Nancy’s not edgy, but she’s not a goody-two-shoes, either. She’s rich and is in many ways working for the status quo, but she is using her privilege to help people. She can go where she wants and do what she wants but her father and Hannah are always there supporting her. Nancy genuinely is a land of contrasts, and it’s hard to capture.

Stratemeyer apparently believed that A Woman’s Place Was In The Home, and he objected to a lot of what fans came to love about Nancy. Whenever she’s toned down in the books from his lifetime, that’s his meddling at work. But in her very existence, Nancy Drew was an inspiration to a lot of women. Yes, she’s contradictory enough that she can be admired by both Sandra Day O’Connor and Sonia Sotomayor, but Laura Bush and Hilary Rodham Clinton. But honestly, Laura Bush’s support of Nancy doesn’t surprise me. She’s a former librarian, and Nancy got girls reading.

In fact, you need look no farther for evidence of Nancy’s legacy than another series we’ve discussed this month. Claudia Kishi of The Baby-Sitters Club reads Nancy Drews. She hates schoolwork, and her entries in the club notebook leave Adult Gillian wondering if anyone ever tested her for dyslexia, but even though her parents didn’t want her to, she read Nancy Drew. You’d think her parents would be happy she was reading at all.