The Godfather I (1972) and II (1974) served as a prelude to a string of mid-70s blockbusters, starting with Jaws (1975). While the Godfather films were complex character studies punctuated by violence, they were commercially successful because they were politically open—they could be read as a liberal warning about how power corrupts (alluding to Nixon and the Watergate scandal) or as a conservative affirmation of loyalty as a family value.

But by making the epic saga of Sicilian crime families more identifiable to an American audience—which the films did in part by emphasizing their assimilation into American society and shedding light on their codes of conduct—the Godfather films risked romanticizing these families to the point where the immensity of their crimes all but faded from view.

John Cassavetes’s The Killing of a Chinese Bookie, first released in 1976 and then in a reedited version in 1978, dared to completely de-romanticize these gangsters, portraying them as ruthlessly venal thugs. Cassavetes went so far as to suggest parallels with the money-hungry Hollywood studio executives who were the bane of his artistic life: both, he argued, were destroyers of dreams. But he was, as for most of his career as a filmmaker, not rewarded for the daring of his vision. Both versions of the film were commercial failures.

In the 1980s, there was a a cynical response to Reagan’s revival of the gospel of prosperity that seemed to furnish a ready-made excuse for all manner of excessive behaviors endorsed by Wall Street. It was therefore an opportune time to revisit a genre that already had a perverse sense of morality—and twist it even further.

The film I will now re-view answers the question: what would you get if you played up the bleak humor of the power struggles in the Godfather films and took in fully the horrific effects of the isolation of the characters?

“You Will Be Even More Alone”: Prizzi’s Honor

(dir. Huston 1985)

Let’s start by looking at the film’s star, Jack Nicholson. The Shining (1980) set the template for his post-70s career by playing up his manic intensity. This would become Nicholson’s default setting. It fit well with the simplified stories and themes of 80s-mainstream Hollywood films that encouraged actors to go big on delivering the emotional goods, and tended, at times, to turn these actors into caricatures, or, even, into cartoons. This came full-circle in comic-book movies like Batman (1989), where Nicholson played the Joker. While Nicholson could be exhilarating when he would explode into rage and fury at any given moment in a film, too often he seemed bored, as if taking on these one-dimensional roles offered little challenge.

By giving Nicholson a more challenging role, Prizzi’s Honor brought out some of his best acting of the decade. As the hit man, Charley Partanna, he dialed the intensity back, reminding us of his wider range demonstrated in 1970s films, such as Five Easy Pieces (1970), The King of Marvin Gardens (1972), and Chinatown (1974). Nicholson seemed to realize that Charley’s deliberation and focus, while necessary for survival in his profession, could blind him to the realization that, like in Nicholson’s role as the flawed detective, Jake Gittes, in Chinatown, he could be two steps behind everyone else.

The script was co-written by Richard Condon (based on his novel of the same name), who previously wrote the novel that was turned into the film The Manchurian Candidate (1962). Prizzi’s Honor has a similar feel to the political paranoia of The Manchurian Candidate, for the brainwashing of a Communist agent to turn him into the perfect killing machine has parallels with the unquestioning loyalty of a mafia hit man. But Condon inserts his own joker into the deck: a love triangle that, by threatening to overshadow the political conspiracies in the mob underworld, makes that world look increasingly like a realm of the living dead.

Charley has become acclimated to the paranoid way of life in the Brooklyn domain of the Prizzi family. In the opening scenes that compress time, we watch him grow up under the watchful eye of the Prizzis and become initiated into the family. This is an important key to the film’s satire—that, for Charlie, everything appears normal.

Yet it seems rather obvious to us that very little could be considered as normal. Don Corrado, played with a decrepit verve by William Hickey, seems, at times, barely functional, his movements spastic, resembling those of a dead frog jolted into motion by an electric charge. He has a one-track mind; his obsession is the family’s survival at any cost.

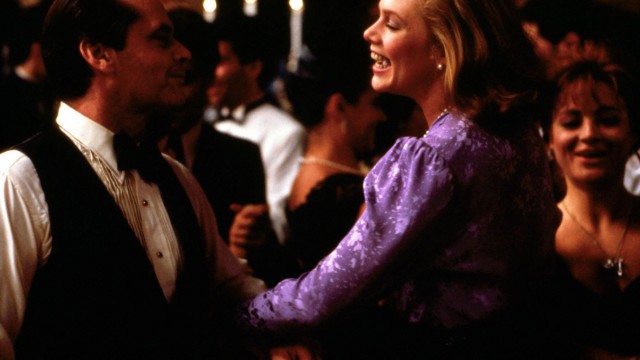

Corrado’s ruthlessness is equaled by the determination of Maerose (an Oscar-winning performance by Anjelica Huston) to get Charley back and reenter the good graces of the family. When Charley falls in love with and marries Irene Walker (played by Kathleen Turner), another assassin hired by the family, they are both subjected to Maerose’s machinations, which are subtle, but effective.

Here, it should be mentioned that another key to the satire is the heavy-handed stereotyping. Played as comic exaggeration, it drives home the point that no one in this film escapes ridicule.

In the role of Irene, Turner accentuates her bubbling charm, a West- Coast ray of sunshine in a bleak East-Coast gangland. Because she is an outsider to the family, Irene has a markedly different perspective, which she tries to convey to Charley. She tells him what her late husband, Marxie Heller, told her about “them Sicilians . . . They’d rather eat their children than part with money and they are very fond of children.”

Charley responds: “If Marxie Heller’s so fuckin’ smart, how come he’s so fuckin’ dead?” Which reminds us that no one is as smart as he or she thinks. Like Irene, for instance. She avoids being implicated when Charley kills her husband for his role in a scheme to skim money from the family. While Irene is rather smart, she is foolish enough, however, to think she can keep some of the money for herself.

Irene is such a smooth talker that, after Charley realizes she has double-crossed the Prizzis, she convinces him that they can negotiate with the family. But Charley and Irene have botched a kidnapping–Irene killed a police captain’s wife who was in the wrong place at the wrong time–which is a serious problem for the family. Corrado figures if Charley kills Irene, then the Prizzis can give her body to the police to settle the matter.

To a degree it all makes sense. Then again, some at the time thought Reagan’s secretly arming the contras in Nicaragua was a good idea.

When Charley is summoned to a meeting where he is told of this plan he is, in effect, crossing the river Styx. He realizes, too late, that to stay in the family will cost him his soul. As he looks around the room in a daze, he now understands he will be alone together with the family forever:

CP: I need her. Look at youse . . . is that what you want for me, to grow old, like youse with nothing but bodyguards and money to keep me company?

DCP: Charley, my beloved man. You will be even more alone if you turn your back on us. We are your blood.

CP: Geez, I feel like I’m drowning or something.

Charley, like Corrado, has become a permanent member of the Prizzis, making him another one of the living dead, and there is no way back.

The downbeat theme, however, did not prevent the film from being a success, both commercially and its being nominated for several Academy Awards, including Best Picture, John Huston for Best Director, Nicholson for Best Actor, Hickey for Best Supporting Actor, and Anjelica Huston for Best Supporting Actress, which she won. Although Nicholson did not win, his star power, apparently, was enough to sell the complex story line that reveled in the ideological and philosophical contradictions of love, money, and loyalty. Prizzi’s Honor is one of the more perfect films for the grey areas of the Reagan years.

The ending is a showdown between Charley and Irene, who has been given a contract by Corrado’s son to kill Charley (in retaliation for his father’s favoring Charley over him). While she appears to be the better assassin, this is Nicholson’s film; thus he kills her. Charley runs back into the arms of Maerose. This is both a cynical and comedic finale—even, love, apparently, exists in this underworld.

And it further twists the code of the family. As long as nothing gets in the way of making money, even disloyalty can be overlooked. As goes Brooklyn so goes Wall Street.