The last era where you could basically just walk into a Hollywood career was in the days after World War I. You could show up at the studio and have William deMille ask what department you thought you should be working in—and when it was proved you didn’t know anything about set dressing, have it suggested that you try out other departments until you found one you liked. Oh, this is doubtless because the person in question was a white person whose parents owned a well-known restaurant next to a theatre, but still. I kind of doubt someone in Arzner’s place would have that kind of opportunity today.

Dorothy Arzner was an alumna of one of the most prestigious private schools in LA. She did two years of premed at USC before eventually deciding that she didn’t want to be a doctor; she wanted to heal the sick, but not if it took, like, actual work. She spent time as an ambulance driver in World War I, admittedly an ambulance driver in LA. It’s still probably work she was only able to get because of the war, as there were fewer men available to do the work.

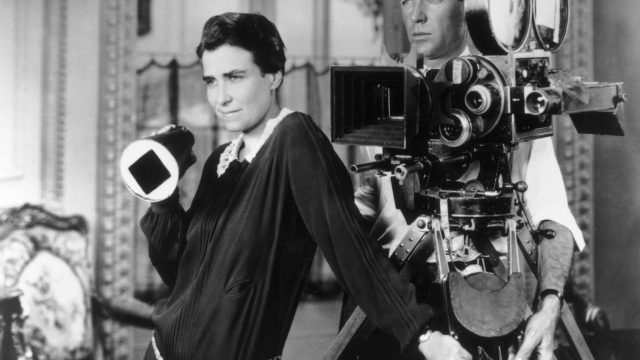

After the war, she felt as though she could pretty much just walk into the film industry. Which it seems was true. A friend I guess knew William deMille and set up a meeting with him. After some observing the industry at work, she recognized that the best job on the lot was as a director, someone who got to tell other people what to do. She started in the script department, however; from there, she went on to be an editor, which she felt was the next step. She eventually had enough pull so that she could tell Paramount to either give her an A picture or else she’d just walk away.

It’s still impressive that she was given the opportunity. She’d been in the studio for eight years, and she’d done good work; apparently her editing of Valentino’s Blood and Sand saved the studio quite a lot through judicious use of stock footage. However, that doesn’t mean she’d have to be allowed to direct a big-title picture. Fashions for Women, now lost, did well enough to launch her career as a director, at least. She was even valued enough at the studio to be allowed to direct Paramount’s first talkie—for which she invented the boom mike, when Clara Bow wasn’t fully comfortable with the stationary sound equipment.

No one seems sure what ended Arzner’s career. She retired from Hollywood in 1943. Some speculate it’s because her movies were no longer as successful. Some say it’s the sexism and homophobia of the industry. Possibly it’s a combination of the two; possibly, there are even more reasons. She would go on to teach filmmaking at the Pasadena Playhouse. She taught at UCLA; Francis Ford Coppola was one of her students. In later years, she directed a few commercials for Pepsi as a personal favour to Close Personal Friend Joan Crawford; that friendship is, of course, one of the reasons people speculate about Crawford’s sexuality. Never mind, of course, that Arzner was in a relationship with choreographer Marion Morgan for forty years and may well have been monogamous. Being friends with someone attracted to your gender means you’re sleeping with that person, after all, right?

Arzner could probably have made a better commercial for my Patreon or Ko-fi than I normally manage?