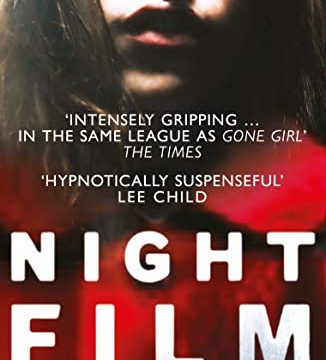

Night Film is not a transcendent experience – rather, it’s a work that does three basic, even cliche ideas very well. Its central structure is a detective mystery, alternating between its protagonist chasing a single question across a large world and the jagged, out-of-order story he picks up about his target. Its central protagonist is Scott McGrath, a cynical journalist who ruined his career trying to investigate famed and reclusive horror director Stanislas Cordova in a highly unprofessional outburst that allowed Cordova to sue him for libel. Scott’s arc is a fairly straightforward one of slowly surrendering his preconceived notions of people and dropping a hardbitten persona (reminiscent of William Holden in Sunset Boulevard) for a more openminded sense of curiosity – I always pictured him as being played by a young Jack Nicholson. Its central mystery is that of Cordova; the question that drives Scott back to chasing him is the murder of Cordova’s daughter Ashley followed up by a rapid and shocking coverup, and Scott is convinced that Cordova is a cult leader committing atrocities and abuse in the process of making his films.

I like to hold Law & Order as the prime example of a work that is entertaining, functional, and knows exactly what it is without ever quite crossing into blazingly original territory. Law & Order is made with an incredible amount of talent and hard work in order to tell comforting and untroubling stories with as few surprises or risks as possible. In the case of Night Film, it feels less like an assortment of thriller cliches (though it is that) as an assortment of traditional motivations for making a thriller, expressed as elegantly and as beautifully as possible. Many thrillers have shot for arcs about someone coming to see the world is much bigger than they expected; few of them have not just managed to radically unbalance their protagonist’s sense of reality but do it piece-by-piece, with Scott feeling a little more out to sea than he did in the previous scene. The climax of the book is a setpiece that isn’t just nightmarish but does, literally, remind me of particularly abstract nightmares I’ve had – one in which nothing specifically frightening is happening and yet I feel a constant sense of dread.

Thrillers have also often shot for a mysterious figure who defies categorisation or explanation while still stringing the reader along as much as possible, and I believe Night Film fully achieves this with Stanislas Cordova. One of the contemporary reviews for Night Film dismisses Cordova’s work as sounding terrible, which aside from sounding like it was written by someone who just doesn’t like horror movies, seems to fall into the exact kind of smug dismissiveness that the book itself pulls apart in Scott. Every now and again, people discuss stories-within-stories and remark that they have to be bad or they’d distract form the main work (or, in extreme cases, that the writer would be making that work instead). My approach to criticism is that the quality of the work is secondary to how interesting the choices the artists make are; this is generally easier with good art but both Ruck Cohlchez and I have written some of our best work on bad artists.

Pessl seems to take the same stance. Scott’s arc would not work at all if Cordova was anything less than an interesting artist, and I find him a genuine visionary based on the descriptions we get of his movies and his process. Pessl’s big particular talent is vivid and memorable details, and as I said this reaches its apotheosis in the climax but fills out things like the mere descriptions of plots in Cordova’s films; I don’t know if I’d like them or even want to watch them in the first place, but they successfully convey someone thoughtful and clear-eyed about the stories he wants to tell with themes that recur not as an affectation but because he’s constantly thinking about and interrogating them from different angles. One of the first things we learn about him is that he gave an interview to Rolling Stone shortly before going into seclusion, but we don’t get that interview – or, indeed, any direct dialogue or ‘onscreen’ appearance outside of a phrase his fans latched onto from the interview – until the very end, and by then he has been built up and up and up so much that his actual words seem fairly simple, before he closes the interview upon realising that he’s not being listened to.

Also, I could totally live without the multimedia aspects.

The discussion post will go up on the 28th of November.