We’ll get to the enormous influence of Who Framed Roger Rabbit? by the end of this series, but that influence was already being felt just a few months after it premiered. The music video for Paula Abdul’s “Opposites Attract” was created by Disney animators to pass time in between projects. You can see they applied what they learned on Roger Rabbit to the creation of MC Skat Kat, who has the same rubbery energy as that movie’s hero. In every other way, though, it shows what made Roger Rabbit so special and so inimitable. The “real world” aims for the urban grit of Roger’s Los Angeles, but it’s just as cartoony as Skat Kat. For the whole runtime,cOpposites Attract never succeeds in making you believe he and Abdul are occupying the same space. The closest it comes is when it recreates a much earlier attempt at merging live-action and animation: the Gene Kelly/Jerry Mouse tap dance from Anchors Aweigh. The fact that this requires Abdul and Skat Kat to be on opposite ends of the floor is no small help there.

Music videos are always going to be glorified advertisements, but this one feels especially mercenary. MC Skat Kat is obviously being played up as a possible merchandising bonanza — the first thing we see is his name on a poster, while Abdul’s real duet partners, the Wild Pair, get no credit anywhere. The single cover doesn’t even have Abdul’s face on it: all Skat Kat all the time. And sure enough, MC Skat Kat got a whole album to rap on a few years later. Predictably, no one wanted to listen to a cartoon cat, and the AV Club named it the least essential album of the decade.

A much more lovable cat is the star of the National Film Board of Canada’s adaptation of the classic folk song “The Cat Came Back.” A little yellow sprite whose expression never changes no matter how much destruction it wreaks or endures, the cat defies every effort by its new owner to get rid of it. Writer/director Cordell Barker wisely recognized the song’s resemblance to the classic blackout-gag cartoon, and he fills it with Looney Tunes-level escalating slapstick as Old Man Johnson gets increasingly desperate to get rid of the cat. And he goes even farther than Plympton on dizzying perspective changes. The “camera” moves with breakneck speed across enormous distances, and it becomes obvious Barker’s doing more than just showing off. These shots may be difficult in animation, but they’d be impossible in live action. And while studio animation often tries to make the artists’ work invisible, Barker draws attention to it in every frame as the squiggly outlines wiggle and shimmer.

Sometimes I get the feeling it comes across I can’t tell the difference between “best animation” and “most animation.” And as much as I love the rubbery, hyperkinetic style of Tex Avery and his imitators, it’s not as easy as it looks. It takes patience, craft, and resources. And Ralph Bakshi, God bless him, did his best to make that style work without any of the above. He was one of the few success stories of the Dark Age: both his X-rated debut Fritz the Cat and his take on Lord of the Rings made it into the year-end box office top ten, not that it impressed the studio enough to let him film the second half of Rings.

But by 1988, he’d burned enough bridges that he was reduced to the Christmas special/failed pilot Christmas in Tattertown. It’d be unfair to judge Bakshi on a TV budget with the megabudget animation of Who Framed Roger Rabbit? But, the fact is, even his features look like this, and Roger’s animation director Richard Williams had no problem packing every frame with motion even for his TV specials and commercials. And anyway, Christmas in Tattertown invites the comparison. The titular setting, where every lost thing ends up, with its combination of Golden Age cartoon zaniness and grungy urban decay, looks uncannily like Toontown. And Bakshi shares Roger’s revivalist spirit: he said, “What I wanted to do was make something where old and new animation could clash head-on, visually, stylistically, and in attitude. Tattertown is where old cartoon characters live side by side with new cartoon characters, and they have a hell of a time relating. … They’re right up against characters who are modern and can’t move very well and have superior attitudes.”

In the end, all the characters were drawn in the same cod-’30s style, and none of them moved right. Instead of Bugs Bunny skydiving with Mickey Mouse, the cameos by animated and comics characters are so obscure it’s entirely possible they’re only for Bakshi’s own amusement: one of the cultists from Bimbo’s Initiation, Sick, Sick Sidney, the Toonerville Trolley, Piggy, Krazy Kat and Ignatz Mouse, Bosko and Honey, and plenty more I’m sure were too obscure even for me. In one scene, he traces a gorilla waiter directly from the debut Looney Tunes short Lady, Play Your Mandolin. The same scene shows Flip the Frog — Mickey Mouse co-creator Ub Iwerks’ failed attempt to prove he didn’t need Disney — complaining to Disney’s pre-Mickey creation Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, “I could have been just as big as Mickey” and it’s about as funny as you’d expect from any joke that needs that level of explanation.

More importantly, “Christmas in Tattertown” suffers from that lack of resources, craft, and patience. Like most TV animation, “Tattertown” was animated “on twos,” i.e., skipping every other frame. That works for less frenetic animation, but when one frame stretches a character out twice as long as the previous, any illusion of life is dead on arrival. Worse, the characters have no weight — it looks less like the classic “rubberhose” animation Bakshi wants to recapture so desperately than shredded paper in the breeze.

The script’s no better. Our nominal villain, a doll named Muffet, gets the short’s one moment of poignance when she arrives in Tattertown and realizes, with tears in her eyes, “I can move! I can feel! I’m free!” Meanwhile, our nominal hero, Debbie, is introduced trying to recapture her liberated dolly, and she’s just as insufferably condescending to everyone else she meets.

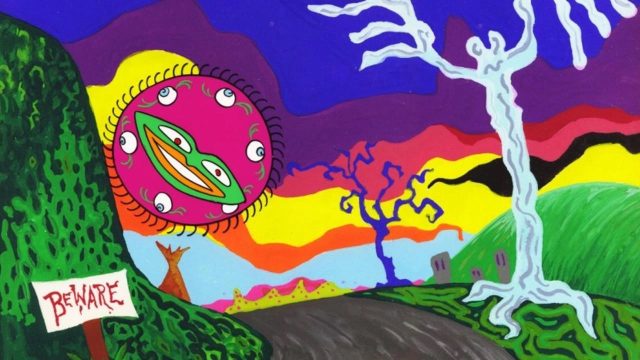

If “Tattertown” represents the low end of what the shorts scene had to offer in 1988, Face Like a Frog is the high end. Give or take Plympton, Sally Cruikshank was as close to a celebrity as the medium had at the time, thanks to her cult classic 1975 short Quasi at the Quackadero. That was a product of the psychedelic ‘70s, but Cruikshank didn’t let her style stagnate. Still obviously the work of the same hand, Face Like a Frog is as ‘80s and Quasi was ‘70s. It looks like it could be a new wave album cover. Specifically this one, which I bring up because it relates to Frog’s secret weapon: Danny Elfman. He contributes both the song “Don’t Go In the Basement” and the wonderfully off-kilter score, combining his usual tricks with some kind of broken-down electric organ that closely resembles the Residents’ God in Three Persons from the same year.

Bakshi and so many other animators have slavishly recreated the surface elements of the Fleischer style. Cruikshank digs deeper, pulling off the impossible feat of recreating the ever-changing, dreamlike atmosphere of the Brothers’ best shorts like Snow White. Elfman even does his best Cab Calloway in between Hi-De-Ho Man tributes in The Forbidden Zone and The Nightmare Before Christmas, and Cruikshank recaptures the sinuous dance movies the Fleischers would trace from Calloway’s performances.

It’s a classic excuse plot — boy frog meets girl frog on a dark road at night, she warns him her house is haunted, he goes in to check it out. I’ve recommended watching animation in slow motion before, but here it’s practically a requirement to catch everything that’s going on. I must have seen Face Like a Frog something like five or ten times now, and I’m still no closer to exhausting it. That breakneck pace gives it a truly unique, unsettled atmosphere, and means the rare clunker — like the scene where the boy frog turns a nut detector on the girl frog’s kooky family, they all turn into nuts for whatever reason, and the momentum stops dead for a second – but, crucially, only a second — so one of them can say, “For what, for what, am I a nut?” — does nothing to the overall experience.

Cruikshank’s figures don’t really have any more solidity than Bakshi’s, but some major differences make that irrelevant. There’s the DIY look that makes any flaw into a virtue — Cruikshank voices the lead frog and is credited as the sole animator. It’s at least as sloppily timed and edited, but that just adds to the handmade charm. The characters seem to talk too fast and step on each other’s lines, but that just turns what would have been limp jokes like, “He looks like my car!” “That’s what they all say” into true dreamlike weirdness. And then there’s the nature of the movements where the characters melt into new shapes so constantly there’s no use conceiving of them as solid anyway. And most importantly, Cruikshank doesn’t lean on borrowed imagery. She has so much of her own, drawing from dozens of sources to create something totally unique, that it’s a pleasure to have her throw it all in your face for five minutes, even if most of it’s only there for a frame.