Popeye begins 1935 in Black Valley, investigating a gang of claimjumpers fed on tainted cactus berries that strip them of their conscience. Popeye comes up with an odd solution, a superhero-comic-esque combination of crossover and continuity. He’ll counteract the mean drug with a happy drug — “Myrtholene — the stuff wich a fellow by the name of John Sappo invented a few years ago.”

Who’s John Sappo? Well, in those days of oversized Sunday funnies, most artists used part of the extra space for “toppers,” supplemental strips running above or below the main action, and other bonus goodies. Flash Gordon, for instance, ran with Jungle Jim, and Popeye had Sappo. Like the main strip, it was quickly taken over by a character who was supposed to be a one-off. Sappo, like Castor Oyl, was a bland little everyman who couldn’t stand a chance against his boarder, the arrogant, hot-tempered inventor O.G. Wottasnozzle.

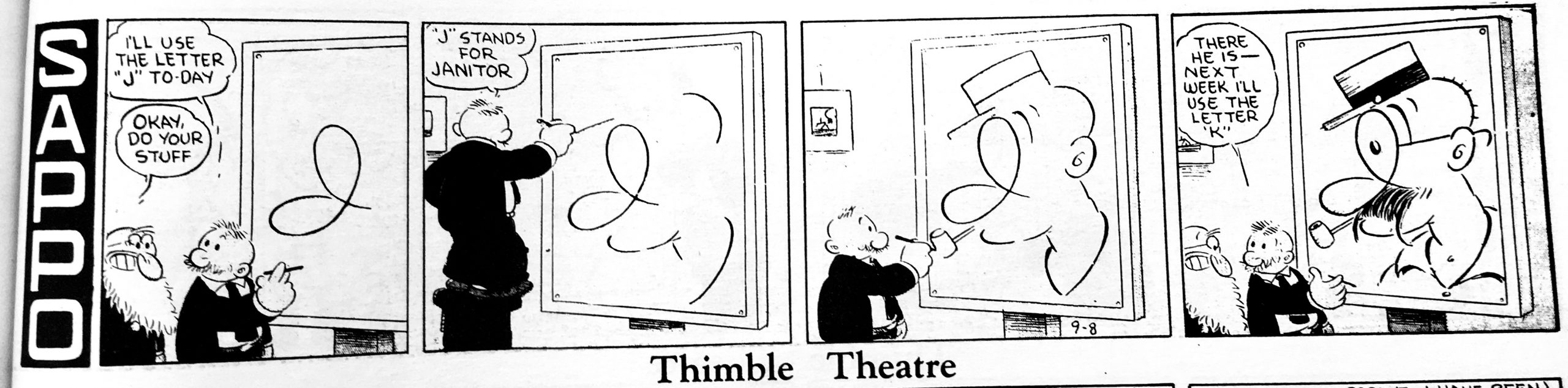

More importantly, Wottasnozzle’s inventions gave Segar years of material. He wrung four months out of the “cell multiplier,” as Sappo’s nose kept on growing week after week. When Bill Watterston envisioned extending the “Calvin keeps growing” for a month to “see how long readers put up with it,” he probably had this story in mind. In one episode, Sappo’s nose even grows all the way out of the comic and into Segar’s art lesson for the young readers.

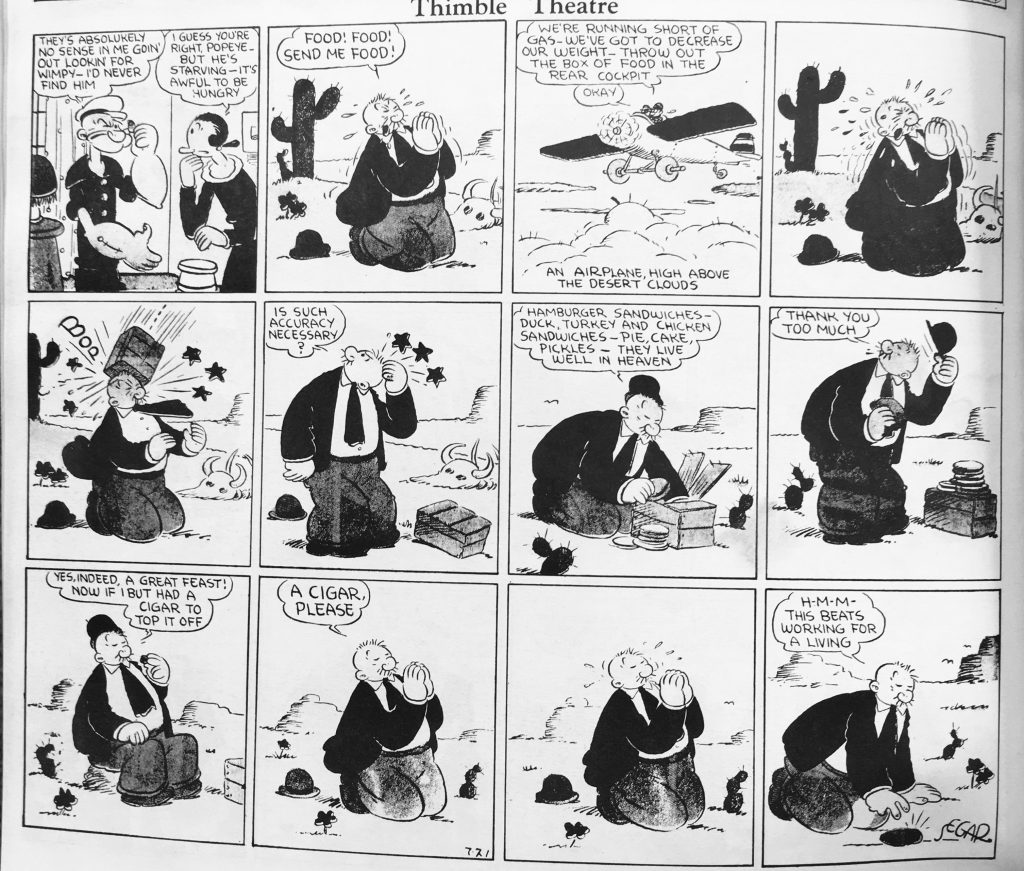

Wimpy gets in on the fourth-wall breaking fun later when he snatches the cigar from his creator’s signature.

Later, Sappo descends into pyschosexual madness when John’s wife Myrtle thrashes him so thoroughly he divorces her. Then she uses Wottasnozzle’s weight-loss ray to adopt a new identity and marry him all over again. It’s just as disturbing as it sounds, and it’s a fascinating glimpse into how taboos have shifted. Segar can’t show a toilet and he calls blood “red ink,” but domestic abuse is apparently A-grade laff fodder — this isn’t even the last time he goes to that well this year. Here’s one especially, confusingly disturbing image, the conclusion to a gag where Olive dresses as a man to see if Popeye’s jealous:

Maybe scared by just how dark he’d gotten, Segar combined Sappo with the art lessons by putting his protagonist through the kind of correspondence course Segar himself had taken. This made more room for Popeye, but it’s hard not to miss Wottasnozzle’s inventions. It’s still a fun exercise in old-time hucksterism, turning Sappo into a showman showing off how he can make drawings out of letters. The other characters react in disbelief, which is a little hard to swallow given how obviously Segar is setting himself up for the endpoint, introducing new characters so Sappo can draw them, switching between cursive and block letters, and frequently warping them beyond all recognition to get to his set destination.

Over in the dailies, Popeye and Castor meet J.J. Gizzik, an eccentric millionaire who wants to charter a cruise to the “Pool of Youth.” Segar hypes up the new story with an opening text blurb that sums up his seat-of-your-pants storytelling style, promising a cast of characters including all the regulars plus, “Alice the Goon may pop up with clothes on.” Alice was the breakout star of the previous year’s Plunder Island storyline, an inhuman henchman for the Sea Hag who introduced “Goon” into the English language. And she does indeed appear, with clothes on — for all of one panel, before Segar forgets about her again. This storyline also features Olive stowing away disguised as a man with a long beard before she reveals her identity at the end of one episode — but then Segar immediately backtracks the next day.

This storyline is a beautiful showcase for Segar’s gift for atmosphere. The only person alive who knows where to find the Pool of Youth is the Sea Hag’s sister, so Popeye and crew stow aboard the Sea Hag’s ship. The Hag herself is one of Segar’s greatest creations, a nemesis worthy of such a great hero. She seems to have been plunked in from a much more realistic strip, and as goofy as Popeye’s adventures get, she remains a deathly serious threat.

The scenes on her ship are drenched in atmosphere, almost pure black except for the characters. The Sea Hag first makes herself known on ominous offstage noises before finally appearing in the flesh, coldly saying, “Good evening folks.” It’s scarier than a direct threat would be, and it’s even more unsettling when she suddenly turns hospitable. At least with direct hostility, you know where you stand. Sadly, Segar never pays that threat off, and the Sea Hag ends up siding with Popeye and crew against a common enemy.

But what an enemy! The sequence introduces Toar, one of Segar’s greatest and most underused creations. Even the Sea Hag is scared of him, and we hear him stomping around the decks for days before he appears. Segar milks the tension, with four panels of Castor hunting down the source of the noise before revealing Toar standing in the dark and silence in a double-wide panel.

Here, again, Segar’s writing gets away from him. Beginning as yet another variation on the Bluto model — or maybe a refinement, since Toar’s a literal caveman — Toar takes on a life of his own, and ends up becoming too darned lovable to fight. Segar exaggerates past bullies’ Neanderthal stupidity and ends up with a childlike character who’d make Popeye look like the bully if he ever beat him. They still fight, of course. Toar breaks the hilariously unfazed Popeye’s neck, which Segar renders looking something like a fleshy zigzag.

Even better is the process of breaking itself, a beautifully kinetic whirl of repeated images like a filmstrip in newsprint.

But then the fight turns into a friendly bout — after throwing Toar overboard, Popeye saves him and the literal-minded caveman returns the favor.

They take five to sail together looking for a dry spot to finish the fight, and once it’s over, they’re best friends — and so they’d remain for the rest of Segar’s life.

We eventually get to the Pool of Youth. It’s a setting full of possibilities — a hidden island ruled by a witch and protected by an army of prehistoric warriors. You can only imagine what someone like Raymond or Carl Barks would do with it. But Segar’s skill with atmosphere is limited to suggestion, not detail. And his distinct style could hamper him — he knew how to draw a funny house and a couple funny trees, but he used them in every supposedly exotic location his characters end up in, so it ends up looking like they never left home.

We never see more than a few rough outlines of the island behind the characters and Segar, perhaps knowing his weaknesses, gets them out of there as soon as possible — they’re in and out in the space of four days, just after Segar spent two weeks on a fistfight. The payoff’s lacking, but the build-up makes it all worthwhile.

After that, Popeye’s back to sea again, getting all cranked up he’s “goner build a ark an’ go pilgrimatin’ like Nora did.” This would end up deciding the strip’s course for the next year. First, Popeye gets his funding from wealthy misogynist Mr. Sphinx (who looks suspiciously like the previous storyline’s Mr. Gizzik). Then, Segar follows the story down a side path when Toar decides to drink all the medicine in Popeye’s cabinet so he’ll be extra healthy for his physical examination and gets laid up for the next week and a half. Wimpy, disappointed he’s left out, builds his own ship, the SS Hamburger, out of driftwood, which goes about as well as you’d expect. From there, Segar goes into some (accidentally?) scathing commentary on the history of colonial exploration. Popeye tries to claim an island until the Prince of Wales informs him it’s already taken. He’s horrified to find Wimpy and Olive have beaten him to his “uninhabited” island and throws them off so he can claim right of discovery. But then he meets a tribe of Indians who have lived there for generations, and, well…

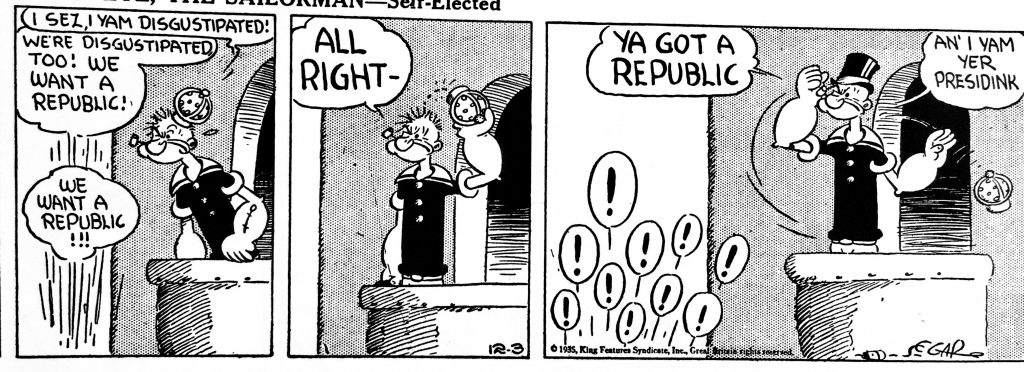

Popeye shows an unexpected dictatorial (sorry, dictipatorial) streak in this storyline, which combines with his unique speech patterns for this disturbing but hilarious moment:

But then Spinachova comes under attack from the neighboring country of Brutia, and Segar’s storytelling kicks into high gear. Adding to Popeye’s odd sense of placelessness, Brutia seems to be somewhere in Europe despite a map placing it in the “South Pafisic” and the Pacific Northwestern Indians inhabiting Spinachova. Anyway, the king of Brutia sends in his seductive secret agent Miss Zexa Peal (who I’d swear was a parody of The Avengers TV show’s Miss Emma Peel if Segar didn’t beat her by thirty-odd years) to learn Spinachova’s weaknesses. She makes Olive jealous, and Segar slows down his normal frantic pace for this funny and oddly poignant silent sequence.

Then he goes right back to the frantic, with a hilarious sight gag where Zexa pulls a Subaru-sized cannon out of her garter.

Zexa convinces Toar to take Popeye out for her by convincing him he’ll be sending Popeye to heaven to “fly and play peeano.”

Instead of the usual punchline, this episode ends with an image of almost Poe-esque terror, with the apparently dead Popeye staring straight at his murderers.

Zexa finally learns Spinachova’s weaknesses, of which there are many, and the Brutians invade. Popeye’s “sheeps” are so useless he has to take on the entire Brutian army by himself. And he does, showing off Segar’s skills at using the over-the-top badassery most modern comics take far too seriously and playing it for glorious absurdity.

All this is foreshadowing for Segar’s most fertile period. (Full disclosure, also the first one I read in full as a kid.) He’d keep the Spinachova plot going as long as he could milk it, then abruptly dropped it so he could introduce Eugene the Jeep, another strange and memorable critter who’d end up immortalized in the English vocabulary. This would lead straight into the creation of another durable character in Poopdeck Pappy (“Popeye’s papa”). More importantly, it led to the apex of Segar’s moody style, with Pappy’s haunted ship and the Sea Hag’s reappearance in the shadow-drenched Mystery Melody storyline. There’s even a shocking amount of emotional sincerity in Popeye’s fatalistic despair when the clairvoyant Jeep predicts he’ll finally lose a fight.

Sadly, Popeye’s career and his creator’s didn’t intersect for long. Of the twenty-odd years Segar drew Thimble Theater, Popeye appeared for exactly ten. After that, Segar died abruptly of leukemia, only 43 years old. In a medium where creators routinely stay with a character for half a century, that’s barely a blip. But we have to imagine he’d be thrilled that his creation, if not his reputation, has outlived him by so long.

Fantagraphics reprinted Segar’s complete run of Popeye twice, first in the late ‘80s and again beginning in 2006, with another edition apparently on the way. The comics discussed here are available in Volumes 3, 9 and 10 of the first series and the volumes Plunder Island and Wha’s a Jeep of the second. (Despite being out of print longer, the earlier editions are much more affordable online.)

And if you want to see a tribute to Segar that frequently outdoes its inspiration, be sure to check out Roger Langridge’s sadly short-lived Popeye series from IDW Comics. Nobody writes Wimpy like Langridge.