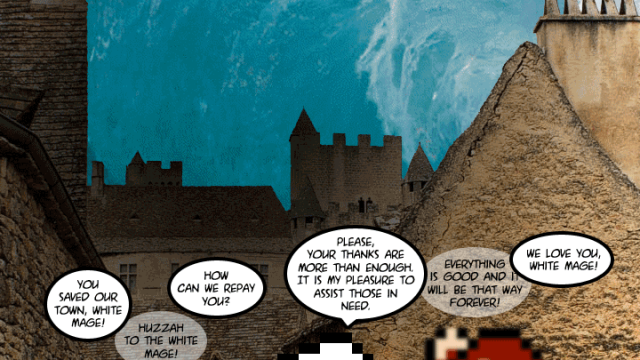

8 Bit Theater is the kind of thing I feel like I never see anymore. In some ways, there was never anything like it in the first place; it’s one of the original Sprite Comics, using pictures from long-obsolete video games for its art, and unlike the other original Sprite Comic Bob & George, it uses both a nine-panel grid construction for each page and manipulated photos for both backgrounds and props. If you’ll forgive analysing the construction of a gag (which you’ll have to, because that’s the point of this whole essay and I’m going to do it a lot and all the time), it adds to the comic atmosphere of the strip in how there’s a jarring dissonance between the ugly, simplistic nature of the characters and the hyper-realistic objects and worlds they interact with. This is something writer/artist Brian Clevinger amps up as he goes further into the comic; he creates not just elaborate but beautiful contexts for the ugly, blocky characters to inhabit, and the fact that he’s putting so much effort into what he’s doing makes the ugliness even funnier.

But it also dives into a kind of comedy I feel like I never see anymore. Irony, I’ve been told for about fifteen years now, is dead, and sincerity has been cool for quite a while now. What’s cool and hip is a general absurdism in which characters express their foibles in funny ways and in which characters speak truth to powerful evil in witty ways – I’m thinking of Steven Universe, Parks & Recreations, and Brooklyn 99 as some examples here – in what was briefly called hopepunk, a name which has died even as the attitude lives on. Ironic detachment has been co-opted by the establishment; ironic detachment is a useless view of the world that perpetuates suffering through apathy; ironic detachment is a view taken by lazy people too cowardly to take a stand on something. These are things I’ve seen hopepunk advocates say, and the bastard of the thing is that they’re right!

It feels to me like cynical humour has taken a serious fall the past decade – of all the cynical comedies I’ve seen, only Rick & Morty manages to tap into that gleeful apathetic everything-sucks spirit, and it basically fell off that in season three and never recovered, due to Dan Harmon being constitutionally incapable of nihilism no matter how much he wishes he wasn’t. Everything else feels like exactly what hopepunks accuse cynicism of being – repetition of jokes that old cynics made without any of their insight in a lousy attempt to sound cool in a way that simply perpetuates suffering. But this is not an accurate description of my favourite cynical comedies. It’s one of those beautiful contradictions in art and life that all of my favourite ironic, cynical, detached, mean comedies were written by people who really, deeply cared about things – who often took offence at the very idea of being called a cynic or a nihilist (shades of Conor’s observations of the contradictions between Walt Whitman and his art). Underlying Blackadder is a moral outrage at the way the powerful have always taken advantage of the weak. Underlying The Venture Brothers is heartbreak at the way the promises of the Space Age and gifted children were broken.

An aside: I have a theory that Bill Murray’s turn as Peter Venkman in Ghostbusters is Patient Zero for the ironic detachment of the Nineties. He really does one of the funniest comic performances I’ve seen in film, as if he’s expending no more energy on the events of the film than he needs to and using the rest of his brain to come up with jokes. These days, people tend to mock Dan Aykroyd for his incomprehensible original script and obsession with generating lore for the series, but this is part of the lightning-in-a-bottle aspect of the original film – Murray needs something just po-faced enough to make his detached indifference both funny and easy to relate to. It’s about as weird to us as it is to him.

8 Bit Theater doesn’t deal with emotions so weighty, but there is a sense that there are things it takes seriously and things it doesn’t, and we’re simply going to concentrate on the latter for the length of this comic. It doesn’t take genre conventions seriously at all; it continually sets up potential for straightforward fantasy storytelling, only to veer off in a more destructive direction, with the most obvious part of that being that the protagonists are, in fact, the most destructive force in the world and largely responsible for the suffering that happens in it. There’s the relentless mockery of its protagonists’ own egos and self-images; Black Mage is the de facto protagonist of the comic seeing as he’s extended the most empathy and often acts as the straight man, and we take tremendous glee in watching his every belief in his own awesomeness, intelligence, or power be eroded by pratfalls and slapstick. Most of all, though, is its mockery of the notion that good things will happen or that life will make sense.

Regular readers will have seen something of a sense of pessimism in my writing. There’s that old cliche that if you’re a pessimist, you will go through life either correct or pleasantly surprised, and I can report that while it’s fundamentally satisfying when it works, it’s not actually that easy. I have often fallen into emotional ruts where every option seems unbearably terrible, where an inability to see a way out has left me paralysed into inaction. But the thing is, that sense of despair doesn’t disappear when I’m riding high either. Pessimism feels baked into my very identity – if you were to take it out, then the things that fundamentally make me who I am and what I like about myself would crumble into nothingness. My most functional self isn’t one who believes good things will happen, nor even one who can keep on keeping on when things go wrong, but who enjoys when things go wrong. This is something that has often baffled people I meet, who keep trying to fix my despair, who keep trying to reassure me that whatever has gone wrong can be repaired, that the world can fundamentally and consistently make sense.

Something like 8 Bit Theater is more comforting. Clevinger’s base principal for the comic is that the funniest thing will always happen – if it’s funnier to have Red Mage’s belief that the world works according to RPG rules turn out to be real, then that’s what will happen, and if it’s funnier to have it not work, then that will happen instead. What this means on a day-to-day level is that ‘living’ in the 8 Bit world means being faced with a deluge of incomprehensible nonsense that is actively, maliciously trying to humiliate and wound you, that these humiliations and wounds can never really be stopped no matter how hard you try to grasp them, and that these humiliations and wounds can be fodder for jokes. Fool on me and Black Mage alike for trying to have egos and beliefs that the world was fundamentally not constructed to prop up; better to take pleasure in our own actions and our own wit, these being the things we can truly shape to be consistently beautiful. My own beautiful contradiction is that the more confident I am, the more self-deprecating jokes I’m willing to make; when you do something not for the result it will get but for its own inherent beauty, failure becomes an option so long as it fuels another inherently beautiful action. In life, as in fiction, you can get away with anything so long as you’re funny.