Maybe we can learn about life via computer simulations, but can we learn to truly live? To laugh? To appreciate the art of Martin Scorsese, Jorma Taccone and Roger Michell (see below, I wouldn’t have remembered either)?

Send articles throughout next week to ploughmanplods [at] gmail and post your favorites from the past week below. Happy Friday!

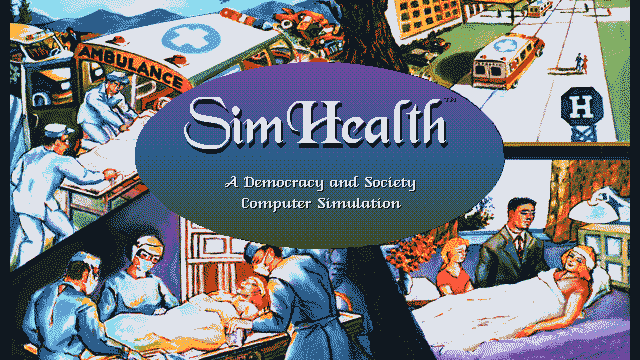

In this week’s most impressive display of research, Phil Salvador of The Obscuritory recounts the rapid rise and fall of the little computer company that, in the wake of the success of SimCity, set out to change the world with simulation games for oil refineries, healthcare reform, presidential campaigns and more:

For many people though, that nuance was lost, and instead they treated it like Maxis could build accurate simulations of the real world. And they wouldn’t stop asking about it. “In the first couple months after SimCity appeared,” Wright told Wired, “we were approached by a number of companies saying, ‘Hey that’s great! If you can do a city like that, we want you to do SimPizzaHut, or SimWhatever.’ We thought these things were so weird that we said no, but they kept coming in. So at some point, as we got big enough, we decided to give it a go.”

Of all the films to be written about on their 10th anniversary, MacGruber seemed one of the least likely at the time of its release. Yet here we are! Alan Sigel at The Ringer does the honors:

Perhaps fittingly, MacGruber’s comically inept hero couldn’t save it from bombing. After making only $4 million during its opening weekend, the movie grossed a total of $9.3 million. But after quickly fleeing from theaters in the spring of 2010, it’s become an ass-kickin’, throat-rippin’ cult favorite.

Maybe people would have understood the movie better if they could have followed Mike Vago and the AV Club down a wikihole about Theories of Humor:

Biggest controversy: Apparently a sense of humor actually isn’t what women are looking for in a man. Killjoy evolutionary psychologist Geoffrey Miller declared that humor serves no evolutionary purpose, and that it “would have had no survival value to early humans living in the savannas of Africa.” Personally, we feel like someone who could do a tight five on what the deal is with hunting and gathering would have been raking in the rudimentary stone tools.

In other correctives to senses of humor, Charles Bramesco confesses to the Guardian that he’s never seen Notting Hill. Until now!

There’s something ineffably late-90s about the notion of Roberts and Grant as sex symbols, particularly in a film that so slavishly worships every detail of Roberts’ visage. It’s partially in their looks, very much of the moment – she in olive-shaped sunglasses and midriff-baring tops, he in artfully ruffled shirts – but more in their essences. They share an erudite connection marked by tentativeness and neurosis, all of which estrange them from a present romcom landscape beset by lumpen Nicholas Sparks adaptations, Netflix’s John Hughes bastardisations, and irony-poisoned deconstructions such as Isn’t It Romantic.

Finally, at the New Yorker Richard Brody revisits the violence and style of Raging Bull:

It’s impossible to see “Raging Bull” without the hindsight of Scorsese’s career since. The connections with “The Irishman” are significant, for instance, both in subject and in style, starting with the flashback framework. Both films involve a Mafia boss successfully crushing the protagonist’s conscience, and include a small but significant element that I’d call “the vanishing first wives.” And, of course, both films star Robert De Niro (whose appearance is significantly altered in both films) and co-star Joe Pesci (his first major role is in “Raging Bull”). But, above all, both films are distinguished by an absence of psychology, a trait that renders them subject to negative judgments from critics with narrow expectations of a character study.