For soul music, the sixties began in the seventies. Make no mistake, the genre was great in the sixties, probably the greatest it’s ever been. But the political consciousness and wild-eyed experimentation that defined the era’s rock were noticeably absent. There were exceptions, of course, but for the most part, soul singers were less interested in being the voice of a generation than recording the best darned love songs and covers they could.

That’s not a knock, either. White artists had the luxury to be bold and different without losing their market share. Black artists could be putting their careers or even their lives on the line by taking the same leaps. When even a song as innocent as “Dancing in the Street” could be denounced as an incitement to violence, it’s easy to see why so many artists preferred to play it safe.

As the sixties closed, though, soul artists seemed to agree the risk was worth taking. Nearly parallel with rock’s turn into safer, more corporatized music in the age of MOR AOR, R&B became more political and individualized. Acts like Love, the Jimi Hendrix Experience, and the Chambers Brothers had proven there was an audience for psychedelic rock led by a black frontman. Others, like Sly and the Family Stone, War, and the two-backed beast of Parliament/Funkadelic fused soul, psych-rock, and jazz into the new genre of funk, heavily cross-pollinating with straight-ahead soul singers like Stevie Wonder. Together with Marvin Gaye’s 1971 classic What’s Going On, the former little Stevie was the unlikely vanguard of this new brand of soul. He transformed himself from a pre-packaged and stage-managed child star to a fiercely unique visionary, musically and lyrically. His album titles from this period like Innervisions and Music of My Mind could double as a description of the movement if it wasn’t so opposed to navel-gazing and committed to exploring the harsh realities of the outside world.

If the risk was worth taking, that didn’t mean it always paid off. The same year, Billy Paul’s label went against his wishes and followed up his smash hit “Me and Mrs. Jones” with “Am I Black Enough for You?” It’s an excellent song, equal parts righteous fury and equally righteous funk. But its militant attitude was too much for the skittish public (as Todd in the Shadows quipped, it turned out “Am I Black Enough For You?” was, in fact, too black) and Paul’s career never recovered.

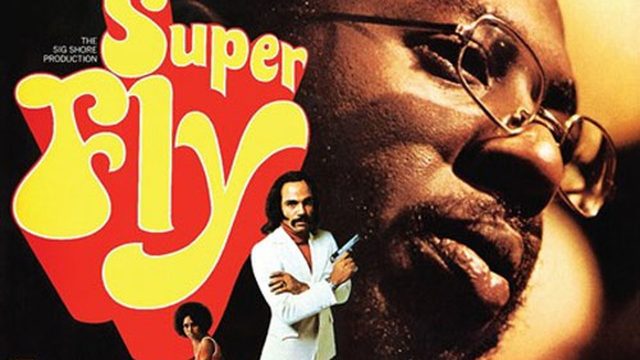

Former gospel crooner Curtis Mayfield had already entered the fray with his solo debut Curtis! But his soundtrack to Super Fly may be the defining sonic and lyrical statement of seventies soul — not bad for an album meant to support a bargain-basement B-movie. It’s almost cliché by now to note how its anti-drug message runs counter to the movie itself. It’s also not entirely true. After all, Super Fly’s Youngblood Priest spends the whole movie trying to get out of the drug trade. Certainly, it’s hard to imagine Mayfield enthusiastically volunteering to score the film as soon as he saw the script, as he reported doing, if he disapproved of its message. Super Fly, album and movie, both save most of the anger for the racist society that made drug dealing the most profitable option for poor black Americans. If anything, the film’s greater emphasis on white crimes, in which the pushers and the police are literally one and the same, has aged better now that Mayfield’s anti-addiction rhetoric has been co-opted by the blatantly racist War on Drugs that would begin over the following decade.

Super Fly even has Priest react directly to Mayfield’s views on drugs when he meets two civil rights activists who more or less paraphrase the album’s message: that narcotics hurt the struggle of black America and that pushers are complicit in their neighbors’ oppression, in Mayfield’s own words, “Pushing dope for the man.” Priest angrily brushes them off, saying he’s not interested in any solution to racism short of full-on guerilla warfare. It’s tricky to say what the filmmakers mean by this scene. Is Priest a mouthpiece for their own views? Do they mean to show his shortsightedness? Or do they not care one way or the other and just want, like the filmmakers (many of them white) who made blaxploitation truly exploitative, to make incendiary statements for the free publicity that will follow their inevitable denunciation in the media?

That said, the album and the movie are at cross-purposes in other, subtler ways too. The movie is celebrated for its gritty realism, but that comes at the price of its scope. By capturing the textures of everyday life, it limits its story to the scale of the ordinary. But the album, fitting the sonic ambition of its contemporaries, blows it up to an operatic, epic scale without ever losing sight of the details, which Mayfield records with sometimes frightening accuracy. “Freddie’s Dead” is the album’s centerpiece, in ways we’ll get to in a moment. But the filmic Freddie is such a minor character he barely even counts as secondary, and his death is shocking in its violent immediacy, but it’s just as immediately forgotten. On the album, it’s an event of cosmic significance, powerful enough to shatter the most resonant myths of the era’s American pride:

We’re all built up with progress.

But sometimes, I must confess,

We can deal with rockets and dreams,

But reality — what does it mean?

Ain’t nothing said

‘Cause Freddie’s dead.

That significance isn’t just in the lyrics. It’s in the music too, in the low, sinister rumbling of the bass and the high, mournful screaming of the violins. Maybe Mayfield’s breadth of vision is the reason so many see a gulf between album and film. The movie is too narrowly focused on Priest to examine the effect his product has on its users, but Mayfield cares about that subject deeply: he devotes just as many tracks to users as dealers (with “Freddie’s Dead” straddling the line, describing Freddie as “another junkie…/Pushin’ dope for the man”). Some, like the title track and “Pusherman,” look at pushers sympathetically, if with more pity than admiration, “a victim of ghetto demands” even if he is “a ghetto prince.” The title track questions the hunger for wealth, not just to get by but at the level of conspicuous consumption, that drives the film:

The aim of his role

Was to move a lot of blow.

Ask him his dream,

What does it mean?

He wouldn’t know.

“Can’t be like the rest,”

Is the most he’ll confess.

But the time’s running out

And there’s no happiness.

But “Pusherman” also provides a more convincing reason: “Got a woman I love desperately/Want to give her something better than me,” tapping into the resonant theme of love as a catalyst for self-improvement that Lou Reed mined the same year in “Perfect Day” when he sang, “You made me forget myself/I thought I was someone else/Someone good.” (Shame I couldn’t find a way to tie him into Snoopy Come Home or I could have gotten myself a Lou Reed trifecta this month.)

Other songs take a more negative view of the “Pusherman,” never more chillingly than the otherwise upbeat interlude, “No Thing on Me” when Mayfield warns that “Our lives are in the hands of the pusherman.” “Pusherman” itself rides a thin line, making the dealer both cool and horrifying in the style of a Broadway villain song, its chugging bassline both seductive and sinister. “In Little Child Runnin’ Wild,” he’s a heartless capitalist who turns away a junkie in the midst of painful withdrawal because he can’t pay: “Can’t reason with the pusherman/Finance is all that he understands.”

But it would be a mistake to limit Mayfield’s vision to that of the film he scores. Both movie and record open with “Little Child,” which, fittingly enough, scores a descent from a God’s-eye view into the heart of the squalid inner city. But even this impressive shot seems too small for what Mayfield’s doing: his operatic sweep seems to demand something beginning miles above the city, shot not in Parks‘ budget-conscious 16mm film but Technicolor Cinemascope, or some kind of flawless virtual-reality technology as yet undreamed of. That sweep from the universal to the specific is reflected in Mayfield’s lyrics, as his nameless narrator describes the troubles that afflicted and continue to afflict millions of people. But at the same time, he adds gratuitous details that make him more than just a mouthpiece, detailing his relationships with his parents and the specific injury that sends him looking to numb the pain and devoting a verse to describing the “one-room shack” where he lives. And I doubt it’s a coincidence that the song’s title resonates with one of the milestones in the development of socially aware, psychedelic soul, the Temptations’ “Runaway Child Runnin’ Wild.” Even more than his forebears, Mayfield keeps the personal and the political tightly interwoven, never wallowing in emotion at the expense of finding political solutions on the one hand or becoming merely preachy and dated on the other.

In the same way, Mayfield’s music is never less revolutionary than his lyrics. The joyous fanfare of the title track combines horns and electrically distorted guitar, jazz and marching band, in a way that blew my mind when I first heard it and immediately sent me running to hear it again and find the rest of the album. I still haven’t heard anything quite like it. It packs an emotional punch powerful enough to sell the movie’s happy ending — and make you forget it’s contingent on threatening to kill a man’s children! “Eddie You Should Know Better” goes just as far in the other direction, with its screaming electric guitar and orchestral strings creating an oppressively despairing atmosphere. “Give Me Your Love” fuses European classical harps and violins with African drums into a soundscape so heavy that, as beautifully erotic as the scene it scores is, it’s almost redundant. And then there’s Mayfield’s own falsetto, gliding angelically over it all. At times, it reaches notes you’d swear the human voice was incapable of. At others, Mayfield drops his voice down to the floor, whispering intimately in a deep baritone.

With his contemporaries, Curtis Mayfield sought to take soul to places it had never been before. Since then, Super Fly’s been pored over by generation after generation of recording artists who steal, magpie-like, whatever bits and pieces they can. But for all their efforts, there’s never really been an album like it since either.

But if you want more articles like this one, all you have to do is donate to Sam’s Patreon!