The trouble I have reviewing E.T. the Extraterrestrial is separating the nostalgia it’s trying to evoke for the genuine nostalgia I have for the film. It’s the first live-action film I can remember watching, in my family’s living room in 1992, which I can still remember even though we moved out in 1994. I was six years old, and boy was I not ready for it.

The claustrophobic opening with the buzzing alien and jangling keys scared me. Elliot looking into his shed at night scared me. E.T., when he finally appeared, scared me. The fact of the frog experiment, once my parents explained it to me, scared me. The sudden, inexplicable appearance of astronauts in the family’s home scared me. And even though E.T. scared me, when he died I started crying so hard that my parents briefly considered stopping the movie before deciding that it would be more traumatic to send me off to bed with E.T. still dead and locked away in that government freezer. And even though I was happy to see E.T. come back to life, I had barely recovered before the ending had me crying all over again.

This movie put me through an emotional gantlet that to this day has never been equaled. A Lars von Trier film festival wouldn’t affect me as strongly now as E.T. the Extraterrestrial did when I was six. So it’s sort of weird that the first word that I reached for to describe the film is “nostalgic.”

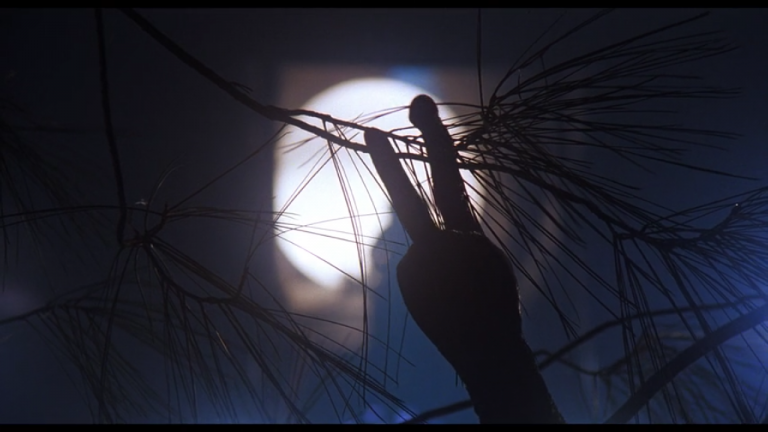

And yet I think that’s part of the film’s genius: it makes us fondly remember our childhood fears, evokes the feeling of looking into a dark woods at night and feeling a chill run down your spine: frightening and comforting all at once. The hazy nighttime lighting that Steven Spielberg captures has a hyperreal quality to it that sells the film’s blending of the suburban with the supernatural. The light coming from the shed is the light of an unexplained alien phenomena; it’s also just the way a bright light looks on a foggy night when you’re a kid with more imagination than experience. To that kid, there’s no real difference.

The film seems to exist in this state of heightened, symbolic reality. The sequences with the government workers looking for E.T. are all motion and diegetic sound, without a single line of audible dialog. The kids’ closet where E.T. hides seems suffused with a red-orange light that has no obvious source. Elliot’s family has no last name.

Spielberg’s filmmaking here seems to have one fundamental principle: identification. In a feat that I don’t hear about nearly enough, he manages to explain the psychic link between Elliot and E.T. purely through editing, without a single line of exposition. Before we even see E.T., Spielberg is having us identify with him, shooting large parts of the opening scene from his point of view. It seems to me that we can also identify with the nightmarish nature of his predicament, too: the whole thing feels like a dream where you’re running toward a door that you know is going to close before you can get there.

A few touches reminded me that this film came along fairly early in Spielberg’s career. I got the sense of a young director feeling out his style, taking things that worked in he previous films and trying to combine everything into a unifying aesthetic. There’s a shot of the neighborhood from an overlooking cliff that uses the same push in/zoom out “Vertigo effect” as the famous shot of Roy Scheider on the beach in Jaws. There’s the pools of light flooding the night landscape from Close Encounters of the Third Kind. There’s even the E.T. prop itself, which almost seems like Spielberg’s attempt to go back to his Jaws experience and get the animatronics right this time.

And yet the final effect of E.T. the Extraterrestrial is how fully formed it seems, how, for all the tinkering he did with the DVD release and all the ideas he could never quite pull off, Spielberg somehow got the exact right scenes in the exact right order. It’s made up of the odds and ends of childhood: D&D, Speak & Spell, Flash Gordon comics, those biting shark things on a stick, sick days, classroom crushes, bikes, Halloween, and friendship, but they’ve been formed into a monument that can still draw that familiar chill down my spine.