“Don’t call me ‘pure soul,’ it irritates me! Underneath this prim exterior there are depths of emotion, romantic longings!” So goes – delivered as a defiant, no-nonsense cry – the crucial line of The Pirate, likely one of the most layered, weirdest, and kinkiest movies to ever come out of classic Hollywood, and certainly from MGM’s Freed Unit. Directed by Vincente Minnelli a few years after his breakthrough, Meet Me in St. Louis, it was supposed to be the grand musical reunion for him and that film’s star, Judy Garland (they had married in the interim), and also for Garland and Gene Kelly, who had co-starred six years earlier in Busby Berkeley’s low-key, underrated For Me and My Gal, which gave Kelly his first movie role. The Pirate is one of the best films that all three were ever involved with, but it was a troubled production – with the music and screenplay being continually changed, Garland in the throes of such intense insecurity and depression that she missed three quarters of the shoot, and MGM chief Louis B. Mayer ordering scenes cut after they were shot – and a commercial flop, having emerged before its audiences as a work of high, knowing camp, a sophisticated farce, a musical that constructed its artificial Technicolor fantasyland to tell a story of sexual repression, awakening, and liberation.

On a remote island in the Caribbean, the virginal Manuela (Garland) is arranged to be married to the mayor of her town, the sweaty, red-faced Don Pedro (Walter Slezak), and in the meantime fantasizes about getting kidnapped by Macoco, an infamous murderer and pillager she reads about in a book with which the film shares its name. On a visit to the island’s port, wishing to get perhaps her last glimpse of the sea – the sight of which smashing against rocks provides an ever-reliable metaphor for the depth and chaos of her suppressed feelings – she catches the eye of Serafin (Kelly), a horny, dickish actor who is so instantly smitten that he invades her town masquerading as the legendary pirate after she initially rebuffs him.

Of all the movies Kelly made in his prime, The Pirate finds perhaps the best use for his noted smarm and aggressiveness, taking both to their comical extremes. In his big song-and-dance introduction, Serafin calls every woman he sees on the street “Niňa,” then explains that he does so because “There are so many beautiful girls in the world with so many names, I find it very confusing. So I simplified things,” which is so brazen it’s perversely disarming. So is the moment, following seconds later, in which he grabs one woman’s lit cigarette, takes a puff while putting his arms around her, flips it into his mouth in order to be able to kiss her, then flips it back out and nonchalantly exhales the smoke. And then, being Gene Kelly in his prime, he finishes off the sequence with a few minutes of breathtakingly controlled sensual dancing that convinces you in a way no words or other actions could. Thus, in the first, but certainly not the last instance of The Pirate having its cake and devouring it too, it establishes Serafin as both the essence of cool and a total cartoon character, the latter quality proving useful when his pursuit of Manuela looks more like stalking.

What helps even more is that, in his pursuit, Serafin is not merely being himself, but also serves as a manifestation of acting and the escape that comes with it. “I despise actors,” says Manuela at one point – but, of course, the reason for that may very well be that she herself has been acting, pretending to be prim and proper and happy about her arranged fate. Yet, in a world where everyone is performing a role for someone else – and that’s what characters in The Pirate do in pretty much every scene – there’s a special kind of acting, the kind that liberates and reveals the truth, and it is this kind that Manuela is afraid of but is even more strongly attracted to. At first, Serafin has to literally hypnotize her in order to briefly achieve this liberation, but he has no power over her when she does finally reveal her unladylike desires. She instantly seizes control, dominating the scene as Garland herself sheds a full decade-plus of her sweet, girl-next-door baggage for a sexually charged, boisterous number, Minnelli’s camera soaking in her energy before effortlessly moving in – and then out of – the kind of hypnotic close-up Hollywood’s Golden Age is revered for.

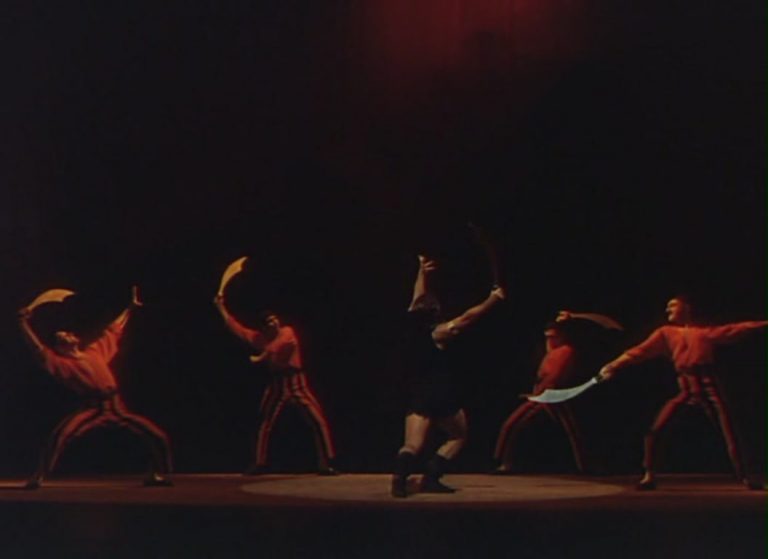

After about an hour of amping up the hothouse atmosphere, the movie unites Manuela’s fantasy of Macoco, her dreams of freedom and her physical attraction to Serafin in its most feverish and lurid sequence, an orgiastic vision of piratedom in which a sabre-wielding Kelly prances around in short shorts amid fire and explosions. One of the most remarkable things about The Pirate is that it’s a deliriously overheated farce that nevertheless takes Manuela’s sexual fantasies and conflicting real-world desires and actions entirely seriously. Early on, exchanges like “Aren’t you interested in love?” “No, I told you I was going to be married!” find humor in her situation while simultaneously underlining its hopelessness from her point of view; and if some of what we see onscreen later is absurd and ridiculous, it’s because that’s how sexuality and attraction are.

Ultimately, Manuela’s fantasies are the source of her agency, and before long, she fully throws herself into acting, first giving Serafin a taste of his own medicine – in a scene that serves as Garland’s greatest-ever showcase as a comedic actress, a rambling faux-swooning monologue where not just every word, but every sound is a perfectly ruthless little turn of the knife – then taking control of the climactic scene by playing the helpless victim. This is the sort of escapism that fits Minnelli, an introverted (and, of course, closeted) aesthete who, for all his versatility as a filmmaker, was perhaps never more at home than when constructing artificial movie-magic worlds like this. The Pirate, like the best of his work, uses that very artificiality to get at something real. In its breathless finale, featuring the great Nicholas Brothers – has anyone else ever made Kelly visibly struggle to keep up? – and a song that would be essentially plagiarized for Singin’ in the Rain, it does so by just blowing everything up and embracing what it preaches. Which, in turn, only makes it that much more joyous and true.