Most of the hotels were closed, the streets were empty, the rowing boats for hire rocked idly at the water’s edge and there was none to take them, and in the avenues by the lake the only persons to be seen were serious Swiss taking their neutrality, like a dachshund, for a walk with them.

– W. Somerset Maugham, “The Traitor,” in Ashenden

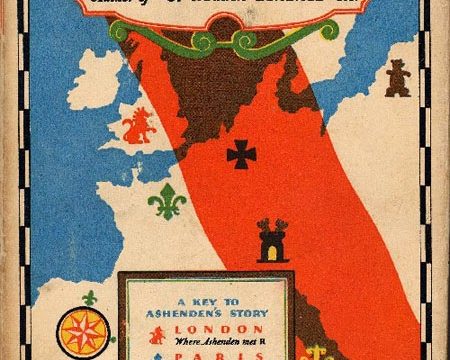

Maugham worked with British Intelligence during World War I and later used those experiences as the raw material for Ashenden, a sort of episodic novel-in-stories about a reserved, capable, and often wryly amused writer-turned-spy. The end result is something like John le Carré strained through Ernest Hemingway: a manly war waged behind the scenes as a series of dry, witty conversations in train compartments and drawing rooms.

These were reportedly a model for Ian Fleming, but there’s very little derring-do here. Most of the more overt action occurs either mistakenly—as when one man is assassinated in place of another—or only on one end of a touch of “The Lady or the Tiger” ambiguity. Ashenden is about espionage as Maugham describes it in his preface: “on the whole extremely monotonous… a lot of it is uncommonly useless.” The great trick, when Maugham pulls it off, is to make the Great Game possess both its odd, pointless triviality and its desperate and sometimes devastating significance.

Maugham’s strength is personal relationship—not romance, necessarily, but more how people relate to each other through conversation and intimacy—and the best stories in Ashenden are the ones that hit that subject hard. Ashenden himself is first and foremost a professional, and his loyalty, as even his superior R. notes, is to professionalism and the spirit of the game rather than to his country. If he can fulfill an assignment, he will. If he can entertain himself, he will do that as well. The conflict between the two, more than anything global, is the real battle here. The moral drama of Ashenden isn’t murder—though there is murder—or betrayal—though there is betrayal—but the doing of clear unpleasantness for the sake of muddied, unclear professionalism.

In “Giulia Lazzari,” for example, Ashenden is put to task coercing Giulia, a dancer, into pleading with her lover to cross into British-allied territory. Her lover is Chandra Lal, a highly successful agitator against the British in India, and Ashenden isn’t particularly opposed to Lal at all:

‘One can’t help being impressed by a man who had the courage to take on almost single-handed the whole British power in India.’

‘I wouldn’t get sentimental about him if I were you. He’s nothing but a dangerous criminal.’

‘I don’t suppose he’d use bombs if he could command a few batteries and half a dozen battalions. He uses what weapons he can. You can hardly blame him for that. After all, he’s aiming at nothing for himself, is he? He’s aiming at freedom for his country. On the face of it it looks as though he were justified in his actions.’

But R. had no notion of what Ashenden was talking.

“That’s very far-fetched and morbid,’ he said. ‘We can’t go into all that. Our job is to get him and when we’ve got him to shoot him.’

‘Of course. He’s declared war and he must take his chance. I shall carry out your instructions, that’s what I’m here for, but I see no harm in realizing that there’s something to be admired and respected in him.’

But, as he says, he’s not here to admire or respect, he’s here to manipulate and be manipulated—knowingly manipulated, by R. and the British Government, as a kind of living tool—and he’s determined to succeed in doing it. His personal connections are entirely ungoverned by politics—at another point, he contemplates an affair with a woman he strongly suspects is a German spy, and has to be officially told off for it—even as his actions are relentlessly governed by them. War, Ashenden shows, is about the misuse of intimacy. All those close-up conversations and all that politeness turned into weaponry. Ashenden’s surface charm is just one more English resource, and because he’s a professional, that’s how he views it himself, at least for the duration of the war.

It’s rare for him to be knocked off-balance, but when he is, it’s almost always because of excess: the excess of orderliness and domesticity that leads Mr. Harrington to fetch his washing in the midst of a revolution, the excess of self-interest that leads to Giulia Lazzari’s only request concerning her dead lover is that she get his watch back so she can sell it, and the excess of commitment that leads Chandra Lal to kill himself rather than fall into the hands of his enemies, the excess of impulsiveness and confidence that leads “the Hairless Mexican” to kill the wrong Greek, the excess of idealism that leads to his proletariat-loving girlfriend refusing to order anything but scrambled eggs (Ashenden effectively ghosts her for this, which I can understand). The point is to be courteous, reasonable, mild, competent, and self-deprecating: anything else is quite simply, and often literally, not English.

‘He’s known as the Hairless Mexican.’

‘Why?

‘Because he’s hairless and because he’s a Mexican.’

‘That explanation seems perfectly satisfactory,’ said Ashenden.

And yet—if there’s an uncanny note in Ashenden that would seem to jar all of this, it comes in “His Excellency,” where Ashenden listens to an English ambassador’s long story of lust and puppy love. The ambassador claims it’s from a friend’s life, but Ashenden rightly disbelieves him: these are just not the kinds of things one knows, and the kind of way one speaks, about another person.

The ambassador, in his youth, found himself briefly entangled with an acrobat he could not respect on any level. He thought her work ridiculous and inept, her looks and behavior vulgar, her mind selfish and limited, and everything about her despicable—except for the fact that she wouldn’t love him and would sometimes seem to not even remember him. He became obsessed with her, and spent the last few months before his marriage traveling with her and begging her to marry him—never mind the nice, agreeable girl back home who was infatuated with him. He only really loved and hated this woman who was predominantly indifferent to him except as an agreeable enough distraction. That passion blighted his whole life and all his subsequent years were spent in a haze of “what might have been” if only he had been able to convince her to love him. His marriage stifles him, Nothing soothes him.

Ashenden refers to all this as the “raw material” of art. As conversation, he doesn’t like it—“Ashenden felt a certain indelicacy in the man’s stripping his soul before him so nakedly. He did not desire this confidence to be forced upon him. Sir Herbert Witherspoon meant nothing to him”—but as an author, he does. It implies the reverse of Maugham’s preface, where espionage is something that must be dramatized into literature; passion is something that must be toned down and structured in order to be bearable. It is untrustworthy—for one thing, in these stories, it’s often connected with women, who do not come off particularly well—and unseemly. But vital: without the raw material, there’s nothing else.

And so Ashenden, always just a little separate, a little ironic, observes it as he observes all other potential dangers. “His Excellency” feels like an intrusion and a wound, and that’s why it works especially well within the context of Ashenden as a whole, and so makes the best case for this ultimately being a novel rather than a true series of short stories. The meaning, as in espionage, is cumulative.