— Lloyd Alexander, introduction to The Book of Three

I’ve only dipped into the slew of YA fiction that’s become a juggernaut in publishing over the past decade. But there seems to be a trend in what I have read, from Twilight to The Hunger Games to Patrick Ness to Frank Portman to the John Green I’ve sampled — the pronoun of choice and the lead voice is the one I’m writing from, the I, the first person. And often in the present tense — all the better for immediacy, to place the reader directly in the mind of the young person telling the story with all his or her passions and anguishes, to mainline angst and feeling in every detail, to dissolve the boundary between reader and the written.

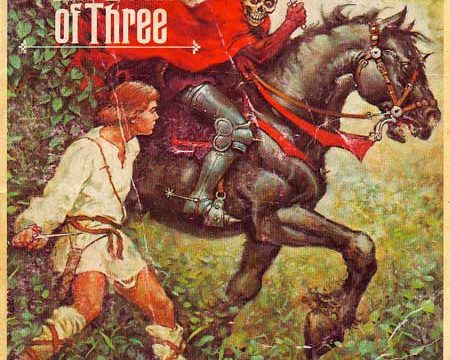

In 1964, Lloyd Alexander began The Chronicles of Prydain, a YA fantasy series that in some ways is entirely contemporary — it’s a series, after all, five books (although most are only about 200 pages) to tell the story of a young person discovering his destiny in a world that is not what he believes it to be. (The first two books were adapted, disastrously, by Disney as The Black Cauldron.) But Alexander tells his story in his own way. Here’s the beginning of the first book, The Book Of Three:

Taran wanted to make a sword; but Coll, charged with the practical side of his education, decided on horseshoes. An so it had been horseshoes all morning long.

Besides the economy of character packed in here — we have a bold young man thwarted by a wiser guardian — there is both wryness and longing in that second sentence, amusement at the ordeal but empathy with the frustration. This is Taran’s story but Alexander’s voice telling it with love and respect, humor and sadness. Repeatedly in the series, Alexander will refer to people weaving a tapestry on a loom and his weaving, the way he tells the story, is inseparable from the actions depicted.

Of which there are plenty! Philadelphia native Alexander served in Wales in World War II and came away with a great love for the country, basing Prydain on Wales and drawing characters and lore from Welsh myth*. Briefly, Taran is thrust into a quest (for an oracular pig! which is one of the things Alexander straight up took from Welsh myth!) and meets many characters, both steadfast friends and dangerous enemies, along the way before a resolution is reached.

Taran is an orphan living on a farm with two guardians and chafing at his status, believing he is destined for something greater if only he could prove it. Coll, with some mockery and more affection, names Taran the farm’s Assistant Pig-Keeper, and Taran’s repeated reference to his status as the book goes on is also both comic and affecting. He is trying to make the most of what he is, and as Alexander hints in his introduction, that is the best we can do, and in the process find out that we are both less than what we think and more than what we thought possible.

This is a journey many young protagonists take, but the first-person that lets us into their minds can also trap us there. Alexander’s third-person lets us know what Taran is thinking (and almost never ventures to any other character’s perspective) but he is ultimately the storyteller. We see the frightening battles with the pitiful and pitiless zombies of the Cauldron-Born and tense passages through treacherous mountain ways through his urgent and unadorned words, and watch Taran’s actions with hope and concern and frustration of our own, knowing his good intentions but seeing his failures clearly, instead of solely through Taran’s filter.

And more importantly, while Taran’s point of view shades our impressions of his comrades, we see them clearly as well. The boastful and brave bard Fflewddur Fflam and his mischievous harp and the cringing and obnoxious but loyal creature Gurgi have their moments of weakness but also of great strength. We can see them as part of a whole long before Taran does — companions that put the lie to a lone hero saving the day. This is something Alexander has in common with Tolkien, but while he never shirks from sadness his tone is less tragic and he believes in humanity far more than Tolkien ever did.

Alexander believes in one woman in particular: the Princess Eilonwy, Daughter of Angharad, Daughter of Regat — the lineage is less important than what it signifies, that Eilonwy knows exactly who she is. She is a princess in the Leia mold who may or may not have feelings for Taran (who may or may not have feelings for her) but is generally too busy telling him what a dolt he is:

“Are you slow-witted? I’m so sorry for you. It’s terrible to be dull and stupid.”

“I don’t mean to hurt your feelings by asking, but is Assistant Pig-Keeper the kind of work that calls for a great deal of intelligence?”

“It must take a lot of explaining before you understand anything.”

This is all from the first few pages where they meet, and it doesn’t begin to touch on Eilonwy’s trademark love of the unlikely apropos simile, like “calling me those horrid names — that’s like putting caterpillars in somebody’s hair.” Alexander clearly adores her as a voice of reason and wit and she and Taran butt heads constantly — seeing this only from his perspective might give us a better view of how he feels, but it’s so much more fun (and fairer to Eilonwy) to observe her with Alexander’s eyes, watching with the detachment and affection to lovingly laugh.

Shortly after Eilonwy and Taran meet, she helps him out of a tight spot. Taran does many things unthinkingly, both good and bad, and he immediately expresses concern that she will pay a price for her assistance. Eilonwy isn’t worried but is touched by his fear: “It shows a kind heart, and I think that’s so much more important than being clever.” Taran never has to worry too much about being clever but over the course of these five books Alexander examines the burdens and joys, the costs and responsibilities, of having and using a kind heart. And his own heart suffuses these stories, giving them weight beyond one young man’s personal journey and holding them down from the weightlessness of myth.

“As for me, what I mostly did was make mistakes,” Taran says at the end of his journey, as he considers how little effect he had on his own quest, which indeed ends in a surprising anticlimax. “Nothing we do is ever done entirely alone,” he is told. In Prydain, joy and melancholy are entwined. Understanding that mixture is called wisdom and that is what Alexander brings this tale and the others that follow. Taran and Eilonwy and the other inhabitants of Prydain have lived in my head for the more than twenty years since I first read (and re-read, and re-re-read) these stories because Lloyd Alexander spoke with his own clear, humourous, sad, wise voice and put them there. I heard that voice speaking to me, not through me, and I have never stopped listening to it.

*Although crucially, not Arthurian myth — but Susan Cooper’s The Dark Is Rising series, also five books and written roughly contemporaneously with Alexander’s, is a classic in its own right, drawing fully on the epic scope and doomed romanticism of that legend.