Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park may have been the highest-grossing film of 1993, but it was also the year of John Grisham. The first adaptation, The Firm, was released in June, followed by The Pelican Brief in December, marking a high point for the attorney-turned-author. Even if neither adaptation was deep, thematically relevant work, the pedigree of actors and directors they attracted was notable.

The Firm, a star vehicle for a young, pre-Mission Impossible Tom Cruise, was ably directed by Sydney Pollack, no stranger to suspense following his 1975 thriller Three Days of the Condor. The same could be said for The Pelican Brief. Written and directed by Alan J. Pakula, this film was his penultimate work (followed by The Devil’s Own), providing thrills while revisiting familiar situations, locations and characters. If you wanted, you could say this movie, more than his last, play as a Greatest Hits Album, echoing some of his best works.

The movie begins by immediately calling to mind a film by one of Pakula’s New Hollywood contemporaries, Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now. The camera, mounted on a helicopter, is cruising a Louisiana marsh at sunrise. We listen to James Horner’s frequently wistful score, an echo of the natural environment we find ourselves in as the opening credits roll.

The music, much like the setting, is soothing, although that soon proves to be short-lived. The score transitions to a much louder shouting and chanting, as we move from a sequence of pelicans to one long, uninterrupted shot of protesters outside the Supreme Court in Washington D.C. The group is protesting a variety of things, from gun regulation and abortion to the death penalty, God and the environment.

We then move indoors, to one of the justices’ chambers. The justice in question, Rosenberg, is wheelchair-bound, and is played by legendary actor Hume Cronyn (who also appeared in Pakula’s The Parallax View). He’s curious about whether any of the signs among the protesters have “my name on them.” He laughs as he hears his favorite one, which asks someone to cut off his oxygen.

His question is directed towards one of the film’s two protagonists, a journalist for the fictitious Washington Herald named Grant Grantham. He’s played by Denzel Washington, who somehow manages to overcome Grisham’s airport thriller name and create a driven professionalism for the character. This is a step up from the book’s characterization of Grantham, which was largely nonexistent. At least here, you can make the claim that Grantham, much like Woodward and Bernstein, doesn’t have much of a personal life because his work is his life, though he may pursue it a little too vigorously, going so far as to stalk an anonymous source with a camera and disguise.

However, Grantham clearly has quite the privileged reputation, given how he’s been left alone in a Supreme Court justice’s chamber, with no communications official in sight, even if they’re speaking off the record. The two are talking about the White House and Grantham’s latest article, which features quotes from “your senior White House son of a bitch,” as Rosenberg colorfully puts it.

Apparently, Rosenberg is largely in favor of “government over the business, the individual over government, the environment over everything,” while giving the Native Americans “whatever they want,” as he puts it. Quoting from Grantham’s article, it became clear how his philosophy places him on no discernible political spectrum of the modern day. But it’s a legal thriller, so we’re onto the next plot point before we have time to mull this over.

Apparently, someone wants Justice Rosenberg and another one, Jensen, dead, and is willing to do whatever is necessary to accomplish the goal. This includes bringing in exotic international assassin Khamel, who clearly is on par with Edward Fox’s titular character in The Day of the Jackal. Played by Stanley Tucci, having fun running through different accents and disguises, Khamel is less of a person than a ghost, especially in the scene when he carries out his first hit.

Though the scenes take place in Rosenberg’s home, we never see Khamel enter the premises. Instead, Pakula has the camera pan from left to right, where we see a sleeping Rosenberg and his nurse watching television. The door opens slightly, but we still see no one. Instead, we hear the near-inaudible sound of a bullet leaving a silencer, and the nurse collapses forward, off his chair. Another shot echoes out as the camera pans in the opposite direction, ending on Rosenberg once again, his pillow and head bloodied from the bullet entering his brain.

Khamel then leaps the fence in a jogging outfit, and dons a pair of glasses and headphones before running away. However, he isn’t running far, sneaking into a gay porn theater, where, disguised as Freddie Mercury (seriously, look at the photo below), he kills Jensen, taking time to eat some popcorn before doing the deed.

The killings of the two justices rattle the nation, especially a law professor who viewed Rosenberg as a mentor. Played by notable playwright Sam Shepard, Thomas Callahan is a fairly straightforward character, talking to his students in class about Bowers v. Hardwick. He ends up getting a retort that the Supreme Court’s justices were “wrong” on their verdict, from his star pupil, Darby Shaw.

Played by Julia Roberts after a two-year hiatus, Shaw might be seen as a character written specifically for the actress. Apparently, Grisham wrote the character in a way that fit Roberts perfectly, and she took the role after reading the book, instead of the script. She is spunky and bright, though her ongoing relationship with Professor Callahan is confounding. While the movie gets credit for calling out the age difference between the two (through Callahan’s friend, an FBI attorney played by John Heard), it still might have played better if they had dropped the whole affair.

Callahan doesn’t last too long, however, getting offed in a car bomb meant for him and Shaw. The culprits aren’t exactly well-defined, but it’s clear they’re being run out of the White House, a souped-up version of Nixon’s Committee for the Re-Election of the President. The outfit, run by the President’s Chief of Staff Fletcher Cole (played by current Scandal-universe president Tony Goldwyn), is eager to muffle a brief that Shaw wrote determining who might have ordered the deaths of the two justices.

The brief, as one might suspect, gets dubbed as the Pelican Brief, creating a host of problems for Shaw. Our second protagonist ends up donning a series of disguises and hotel rooms in order to avoid detection by Cole’s outfit. Needless to say, it’s only a matter of time before she finds Grantham and the two partner up to find evidence backing up her brief. As it turns out, the culprit responsible for the deaths of the two Supreme Court justices is none other than a wealthy donor to the President’s campaign. We never see him, but he remains a prominent force, akin to the Koch Brothers’ network in terms of power and influence.

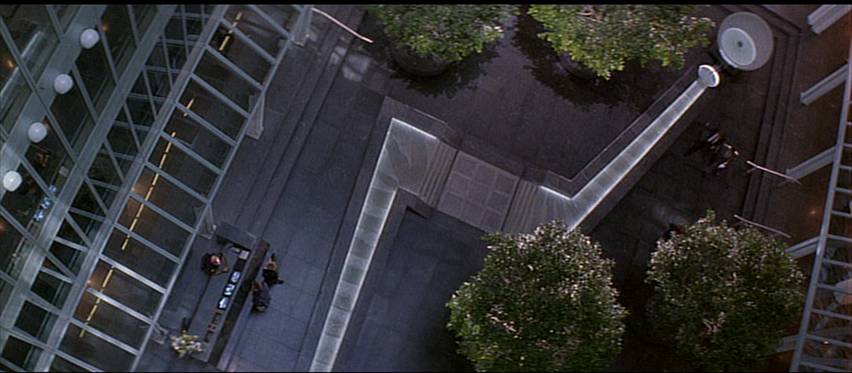

While the film may attempt to prove its bona fides as a statement on politics, the law and corruption, its first aim is to entertain. Fortunately, Pakula is more than capable, taking advantage of the setting and story to play around with motifs from his past works. From the labyrinthine architecture of a culpable law firm (shades of The Parallax View’s dizzying vistas) to Horner’s score, at times an echo of Michael Small’s work on Klute, this is a movie worth seeing at least once to notice all the callbacks, even if the end result is overdone and inferior to its predecessors.

Pakula, unlike some of the movie brat directors who rose to prominence in the same decade, had worked for the studios since the 1940s. He slowly climbed into the role of director after working as a producer, overseeing the filming and post-production of the 1962 film To Kill a Mockingbird.

While he has directed a number of different movies, his “Paranoia Trilogy” has remained his calling card, with their plausible conspiracies, moody imagery (thanks in large part to cinematographer Gordon Willis) and downbeat endings. Much of The Pelican Brief doesn’t work (why shoot the justices instead of framing their deaths to appear natural?), it does work as a swan song for the director.

Those in power may commit dark deeds, as Pakula seems to suggest in his movies, but as The Pelican Brief shows (if a little too optimistically), the truth can still be uncovered, provided those doing the digging persevere. As Jason Robards says in All the President’s Men: “Go on home, get a nice hot bath. Rest up, 15 minutes. Then, get your asses back in gear.”

Note: For those interested, here’s a more comprehensive essay on Alan J. Pakula.