This is a follow-up to my lengthy article about Mike Mills’ 20th Century Women (which itself is a follow-up to two other articles I also wrote about Mills’ work here). In this piece, I will compare the film’s shooting script to its final form, and hopefully get even more insight on what makes the film work as well as I believe it does. Thanks so much to everyone who has been reading and complimenting these, and I hope you like this one too.

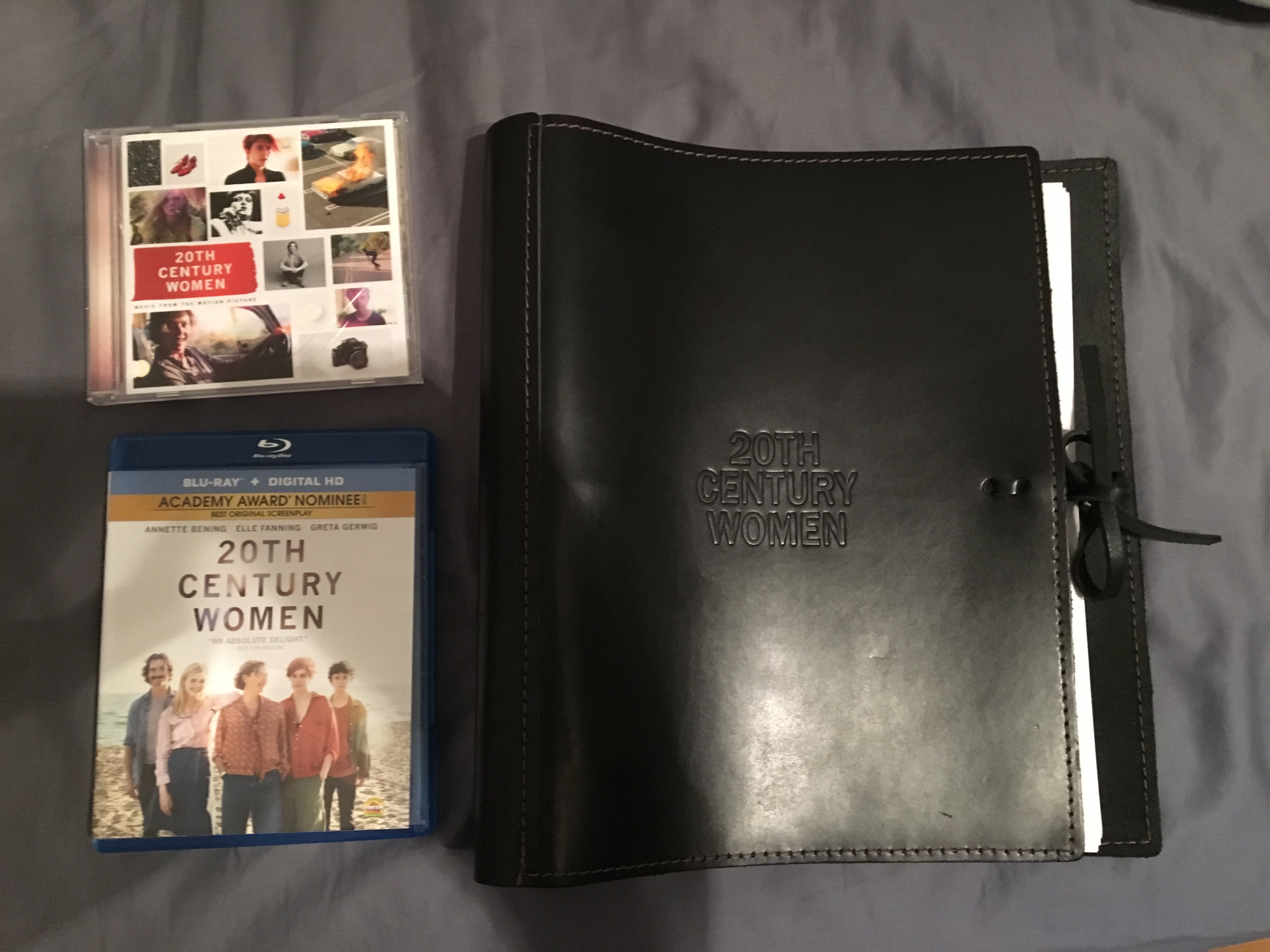

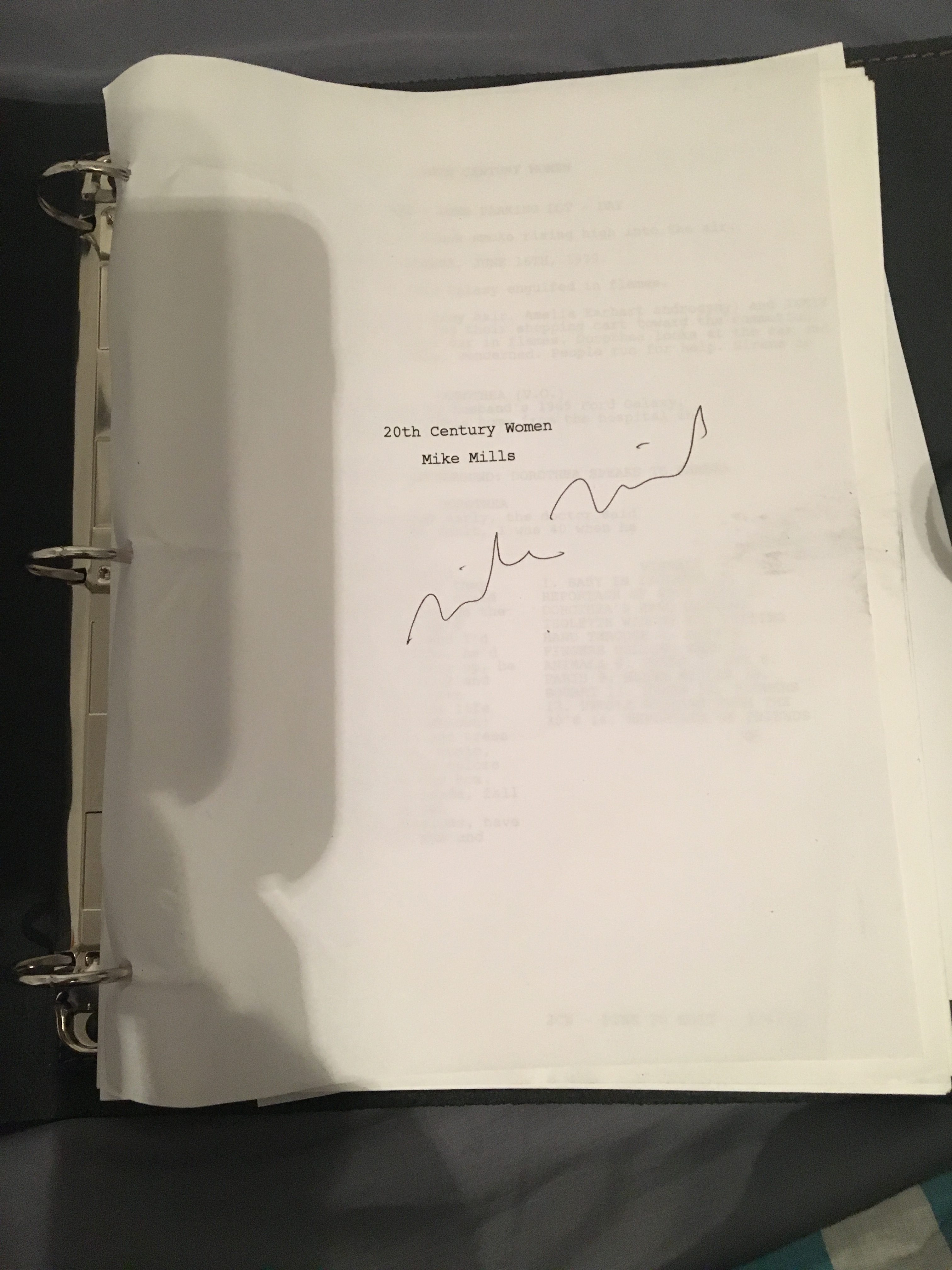

In what remains a travesty for the ages, the only Oscar nomination 20th Century Women received was one for Best Original Screenplay. But A24 must have been campaigning that screenplay hard for awards attention, because floating around the internet are many copies of the screenplay (complete with a handsome leather cover with the title etched into them, and Mike Mills’ signature on the title page, both shown below) that were sent out to Golden Globes (and presumably other awards) voters. Once I found out about this, I most definitely asked for one for Christmas, and lo, I did receive one and read through it that night.

The Basics

Obviously, the premise, characters (besides Julie’s last name being “Bowen” here and “Hamlin” in the film), and general relationships are pretty much unchanged from the script to the film (as fun as it would be to read a totally different version of this script, maybe even the original Oh Wow, Oh Wow, Oh Wow version, I don’t blame them for giving awards voters something close to the “real thing”). And many scenes in the script proceed almost exactly as they do in the film, even the dense montages. If one thinks, due to the film’s fragmented construction, that it was “made” in the editing room, a look at the screenplay will put that thought straight to rest, with Mills exhaustively cataloging the material to use in the montages.

The Car (pages 1-3)

It takes three pages for the first major departure point to show up between film and script. The first two pages mostly function as the first moments of the movie do, barring a little more material in the script for Dorothea’s voice-over about Jamie’s birth (we find out he was born premature, possibly due to Dorothea being 40 when she gave birth) and Dorothea narrating the whole thing, whereas she and Jamie share narration duties in the film. And then we hear about the car, the 1965 Ford Galaxy that belonged to the father. In the film and script, the car is set ablaze at the beginning, an amusingly literal way of opening with a bang. In the film, however, after that opening, the car is not dwelled upon, its symbolic value left unsaid. As for the script, at the top of page 3, we get this:

DOROTHEA (V.O.)

The car was made out of raw materials extracted from mines in South America, China, Africa and North America. Iron, aluminum, copper, rubber, steel, petroleum products, cotton, plastics, vinyl, leather and glass. All transformed into over 20 thousand separate parts, by over 200 separate people in factories in Indiana and Michigan.

And then this (being read over shots of a landfill):

DOROTHEA (V.O.)

Our Ford Galaxy and all of its parts will be buried with all the other trash from Santa Barbara in the Tajiguas land fill, up the 101 just north of Goleta, overlooking the Pacific Ocean.

20th Century Women is not a streamlined film, but the finished film doesn’t really have any digressions on this level. Its voice-over, barring Dorothea’s beyond-the-grave knowledge of the sociopolitical climate of the world from the 80s on, generally stays within the confines of the characters, used mostly for Dorothea and Jamie to share what they know of others and each other. This kind of sprawling detour seems more at home in Beginners, where more of a focus was on the seemingly unconnected events occurring around the characters rather than to them. So I can definitely see why Mills cut it, and I don’t need it in the movie. But still, there’s no better showing of Mills’ massive empathy than him giving an epitaph to an old, kinda junky car, as well as paying tribute to the people who helped assemble it (whose jobs would eventually be lost).

The Voyager 2 (pages 13-14)

For the next ten pages after that, the script proceeds as the movie does, with the same scenes in the same order. Some of the scenes have some dialogue changes (the one with Jamie and Julie in bed for the first time has completely different dialogue than the filmed version), and the script adds a new photography project for Abbie, where she takes photographs of everything she sees on TV (I presume this is why a piece of Roger Neill’s score is named “Everything on Television”), but there’s no real shocking additions here. And then, on page 13, we are hit with the single most “out-there” piece of the script. It goes from shots Abbie took of her TV to a shot of the stars, and then this:

PROPER ENGLISH VOICE

To all those who exist in the Universe, Greetings.We move through space, hearing greetings in different languages with subtitles, (Japanese) “Hello, how are you?” (Greek) “Greetings to whoever you are. We come in friendship to those who are our friends”. (French) “Hello to the world” (Nynja) “How are all you people of other planets?” (Korean) “How are you?

JAMIE ON GREY SPEAKS TO CAMERA

JAMIE

We are the most modern people there have ever been.

First off, I’m glad Mills ditched the direct-camera address idea for the film proper, because that probably would’ve tipped it a little too far into archness. And the same can be even more strongly said of what came before that, and the continuation of that on the next page:

JAMIE (V.O.)

In 1977, NASA sent Voyager 2 into space with a golden record that explains life on earth to potential extra terrestrial life.THE ACTUAL NASA IMAGES FLASH BY

JAMIE (V.O.)

Autumn leaves, a supermarket, rush hour, sex organs, an elephant, how we lick. An old man with a dog and flowers, a man, a woman, planets.

And that is followed by a fast-motion montage which includes footage of the Voyager rocket juxtaposed with Asteroids (even if there wasn’t actual Koyaanisqatsi footage in the movie, I could read this section and instantly know that Mills is a fan of it), this TV ad, footage of 70s duo Shields and Yarnell miming robot movements, and Jimmy Carter saying this:

This is a present from a small, distant world, a token of our thoughts and feelings.

And all this comes back later. This really feels like it belongs in Beginners (I can perfectly hear Ewan McGregor reading that list of what NASA sent in Voyager), and it was wisely cut out of this film. The film already strikes a beautiful, tricky balance between the modesty of its individual scenes and the scope of its grander picture, and having this in here, even done well, feels like it would tip the balance too far in the direction of the larger scale. And this has the potential to go wrong; its insights about what humanity decided to show to aliens of their existence (and its relation to what Mills has decided to represent with his characters and the footage he’s selected) could very easily tip into outright pretension (just look at Men, Women & Children, which also used the Voyager mission as a grander metaphor in the middle of a grounded suburban ensemble and fell flat on its face doing so). It’s nice that Mills went this far out on a limb, but the film is likely better for exploring the world around the characters less bluntly.

The Fainting Game (pages 14-27)

The Voyager 2 business is also a lead-in to one of the other biggest chances from script to film. In the film, the “inciting incident” is ostensibly Jamie getting knocked unconscious for a prolonged period of time after participating in a dumb game where he breathes hard and another kid pulls on his diaphragm. That Jamie could do something so stupid, and the subsequent thought that she has no idea who her son really is, encourages Dorothea to get Abbie and Julie to help “raise” him. But the incident is told in a fast-motion montage of no more than ten wordless shots. It has the same impact in the script, except it lasts a full 13 pages. Two pages are devoted to getting Jamie’s limp body from the skate park back home, with William taking his vitals and trying to resuscitate him and Dorothea reacting in horror to seeing her son in this state. Seven pages are spent with Jamie in the hospital, mostly after he wakes up and is helped through the battery of tests by Dorothea (the finished film, meanwhile, leaves the hospital immediately after Jamie wakes up). And then there’s two more pages dealing with the aftermath, including a scene where Jamie and Julie recreate the incident for Dorothea and Abbie. That’s a strong scene, especially for Dorothea’s understandably horrified reaction to her son so effortlessly recreating the closest he’s come to death. And it ends with this nice, if maybe on-the-nose summation of their relationship;

JAMIE

I live in a different time than you.DOROTHEA

I’m alive, in this time, with you.JAMIE

Not really.

Still, while I like this scene, I can’t say the film is lacking for not having it, especially when it’s replaced in the film by the painful confrontation scene in Jamie’s room between him and Dorothea, which gets the point across perfectly. And most of these scenes are similarly not really needed, particularly the ones before Jamie gets to the hospital, which take the long road to accomplish what the film does in seconds with no words. Admittedly, the scenes in the hospital aren’t really replicated in the film (there’s nothing in the film like the unnerving bit of Dorothea trying to talk to a barely-with-it Jamie), but putting all of them in would put too much emphasis on the incident itself, rather than the effect it has on Dorothea. In the film, this event is a means to an end, but here it’s an honest-to-god Plot Point, and I don’t think it needs to be.

Cutting this material also has the effect of moving up the biographical montage for Dorothea. In the script, it comes right before the scene of Jamie leaving the hospital (it’s mostly the same as in the movie, minus some deleted detail and one bit that was moved to a separate voice-over), and it was moved up in the film to come after the scene of Dorothea’s birthday party. I think it works better there, with the image of Dorothea blowing out her candles providing a neat and beautiful transition into her past, whereas the script precedes it with a seemingly inconsequential scene of Dorothea helping Jamie through getting blood taken. But I must admit that that scene is the one from this extended sequence that I do genuinely wish was kept in the movie. It’s short enough as to not gum up the film’s momentum at that point, and it ties in beautifully to several of the film’s themes, namely the beauty of the small moments in life, the way we’re influenced by what came before us as much as what we’re experiencing now, a mother’s neverending worry for her child, and the everlasting appeal of Humphrey Bogart. It is transcribed below:

Mid blood pull – Dorothea helps distract Jamie while the nurse pulls vial after vial of blood from his arm.

DOROTHEA

Why’d you come to Casablanca anyway?Takes a beat for him to remember.

JAMIE

My health, I came to Casablanca for the waters.DOROTHEA

The waters, what waters? We’re in the desert.JAMIE

I was misinformed.They get real, look each other in the eyes. She cries.

JAMIE

You don’t have to worry about me.That just makes her more worried.

WILLIAM SAUNDERS (Born 1939)

From there up to a certain point near the end, the script basically proceeds as the movie does. But the changes in its middle section are largely weighted towards one character in particular, William. As I talked about in the last piece, William is Women‘s most elusive character, always proving the viewer a little wrong when they think they have a read on him, even about his place in the film; is he the background comic relief, as major a player as his co-stars, or something in-between? One of the more surprising parts of the script is that it answers that by bumping up William’s role so that it’s roughly equivalent to Abbie or Julie’s, right down to him it giving him a birth year and last name at the top of his montage. Just on the level of the movie being called 20th Century Women and not, I dunno, 20th Century People, it was a wise decision for Mills to slightly scale back his role, even before getting into the specific scenes with William that were cut.

The first change to William comes very early, with him getting a little introductory moment in the first post-opening scene. In the film, that scene shows Abbie and Julie going about their days, with William popping up only when Julie comes in the Fields house and sees him tearing down a wall. But here, after the Abbie and Julie moments, we get one with William taking a girl back to his room after fixing her car. This moment is swallowed into William’s montage in the film, and I think it works perfectly there, and I don’t really need the tiny moment after that of him exchanging an awkward glance with Abbie.

The substantial additions to William’s character only start popping up with the sequence of Jamie’s unconsciousness, where William demonstrates professionalism and grace as he handles Jamie’s lifeless body. This already feels like it’s tipping William’s character a different direction than in the finished product, with his heroics putting a fine point on him being a Good Guy, as opposed to him being just a Guy at this point in the film. And after that, on page 33, we get the first big “new” William scene, where he takes Dorothea out in a remodeled 1939 Ford. The reveal of him having fixed the Ford was also pushed into his montage, but the rest of the was not, as he offers Dorothea a joint and has to calm down the drivers behind him, and eventually Dorothea, when the Ford inevitably breaks down. Of course, him taking her out for the night is much more than just him wanting to test the car, and the scene is really there to show his affection for Dorothea and hurt when she rejects him at the end of the scene. It even leads directly into the role-playing scene with William and Abbie, which is now positioned as a rebound fling to get over Dorothea. Now, as amusing as Dorothea smoking pot sounds like it could be, I’m very glad this scene was cut, because it dilutes the power of the later moment of William kissing Dorothea at the bar, which is all the more effective for how it almost seems to come out of nowhere (and it’s strange for Dorothea to react as baffled as she does in that moment if she’s already had a failed night with William). And it also seems to position Abbie as explicitly William’s second choice, as does another added scene of them cuddling after Dorothea and William fall out late in the film (an added thread in the script, and part of an overarching trend I’ll get into later), sort of cheapening their relationship from what it is in the film.

I will say this of one of William’s added scenes; it validates a statement I made in the last piece. Right before Abbie makes menstruation the topic of discussion at Dorothea’s dinner party, William and Julie, a pairing hardly explored at all in the finished film, talk with each other, and Julie tries to psychoanalyze William’s inability to stay with one woman. But she soon realizes that William is more of a mirror than a subject, and Mills follows that realization with this direction:

She now asks more honestly, more vulnerably – looking into her future?

And I said that William “almost functions as Julie’s Ghost of Christmas Future” in that piece, so I’m even more connected to Mills’ vision than I thought I was. Of course, the fact that I got that point loud and clear without this scene or really any extended scene between Julie and William tells me that it’s probably okay that it was cut.

ROBERT FIELDS

The most important distinction between Beginners and 20th Century Women was that while Beginners gave time to both parents, Women completely does away with the father. He’s not named, only seen as a tiny, barely-discernible reflection in mirrored sunglasses, and mentioned only in terms of him scratching Dorothea’s back while she does the stocks. The script mostly sticks to this, in that he’s still definitely not a character in the movie, and there’s no added scenes with him, I dunno, trying to win Dorothea back or some bullshit. But he still manages to have a stronger presence in the script despite his continued absence. Most notably, we find out his name, as seen above, and the origin of his relationship with Dorothea (he played hooky with her in high school), and we’re even told that we see him with Jamie in the opening montage. But while that’s the extent of his actual presence, he keeps popping up in the script, with added moments of Dorothea telling Jamie’s doctor that he went to prison for mail fraud after the doctor prods them about his absence and Jamie telling a maid that his father died in a plane crash. Plus, there’s an entire added scene where Jamie interrogates Dorothea over the reasons she broke up with him. None of the scenes are needed, and it all ends up feeling like Mills putting too fine a point on something that works better only faintly explored. His absence is felt enough just in the existing character dynamics that more mentions of him just feel shoehorned in, or even actively intruding on the titular trio of women.

What’s Missing From the Script

Almost all of the scenes that are in the movie are also in the script in one form or another. But there are two, maybe three, key scenes in the film that are left out of the script. The first is the first scene that Abbie and Jamie share, where they listen to The Raincoats together and try to explain their appeal to a baffled-but-intrigued Dorothea. In the script, this is replaced by another Abbie-Jamie-Dorothea scene, where Abbie shows Jamie her television-based art project while Dorothea watches confusedly through the door, which covers the general bases of the scene in the film and does so without dialogue. But I find the scene in the film richer, for how it deepens the later portrait of the punk scene and how it better sums up these characters’ dynamics. Dorothea isn’t merely observing the modern world and not getting it, she’s actively trying to understand it, and also intimidated by the ease at which Abbie and Jamie explain it and how entrenched they are in it. And her frustration with her own lack of understanding leads beautifully into the next scene not included in the script, which is Jamie’s montage. That roughly replaces the whole Voyager 2 business in the movie, leading into the fainting game, and I think it works much better this way, for how it more simply and directly gets across the point of Jamie being born into a confusing, complex world, and for how it allows Dorothea an omniscient perspective on their relationship, which better suits the film’s generosity in structure.

But perhaps the biggest absence from the script is the scene where Julie talks frankly to Jamie about why she behaves the way she does (this is the scene with “Because half the time I don’t regret it”), which there is pretty much no equivalent scene to in the script. I guess I sound like I’m advocating for “tell, don’t show” in this section, but I really do think you need this scene to throw Julie’s character into clearer light, to make sure that the audience isn’t too quick to brand her as a dumb teenager or self-destructive despite her seemingly welcoming those descriptions. Without this scene, Julie becomes a little rudderless as a character, and none of the added scenes with her really paper that over.

The Sadness

One of the things I love most about 20th Century Women is the balancing act it pulls off between the devastation of what lies in the future for its characters and everyone around them, and the pure joy of the individual moments they experience. It’s a very sad movie, and yet it’s also strangely uplifting. And my admiration for that balance has only increased since reading this script and realizing that Mills didn’t even fully pull it off until late in the game.

The single biggest change the script makes isn’t additional character shading, scenes, or subplots, but a more general, overarching trend towards the melancholy side of the story. The script presents an even sadder movie than what made it on-screen, in ways both big and small.

The most glaring examples of this are all centered around Abbie. The first is the script’s treatment of the roleplaying scene with her and William. In the film, it starts as awkward comedy as they assume their roles and then turns into something more melancholy, but the script version is all melancholy, the “roleplaying” cut down to William tersely taking Abbie’s picture (with a real camera, as opposed to him just using his hands to simulate one in the film) and saying “I’m sorry” before they fuck. But the even sadder changes come later, with Abbie’s two visits to the nightclub. The first one, where she gets in a fight with someone she antagonized before going to New York and gets dumped by William, is seen only in flashback in the film, made comic by Abbie/Gerwig’s matter-of-fact delivery of the events and the gaping ellipses in her version of the story (we never do find out why she smashed that chair). But this scene in the script plays out both in full and in-sequence, both of these changes muting its comedy in favor of its sadness. It immediately follows the monumental bad vibes of Dorothea’s voice-over about punk’s death and her own death (whereas the filmed version has the comedic buffer of Abbie finding Julie in Jamie’s room before she tells the story), and the whole scene is a lot uglier when played out in its entirety, with all the spitting and brawling intact (and yes, we do find out why she smashed that chair). And when she freaks out at William when he breaks up with her after that, her response isn’t a crescendo of “I don’t like you!”s but a less hysterical, and in turn less funny, “Jesus, are you kidding? I don’t even like you.” God knows that doesn’t translate into gif form as easily or wonderfully.

The second club visit, when Abbie takes Jamie there, is similarly shifted. In the film, Mills breezes through it and creates a highlight reel of sorts; Abbie teaching Jamie how to flirt, them dancing and generally having fun together, and them bonding a little at the end of the night. In the script, it goes on longer and almost every single addition is kind of a bummer. For one, there’s a reminder of the disastrous first club visit, with the girl Abbie fought with looming in the background, making clear, as the script says, “[t]here’s no escape” for Abbie. And the girl Jamie flirts with (played by Alia Shawkat in the film) is painted as another foil to Abbie, someone who looks up to her despite Abbie not really liking her in return (in fact, Abbie “kinda hates” her). The night they all have together isn’t nearly as fun as it appears in the film, too; we get an extended scene where Abbie lets Jamie drive drunk (briefly mentioned but not shown in the film), and in turn gets to feel like “a neglectful mom”.

Going along with the sadness is an added bitterness to the character relationships. These are still nice people who get along most of the time, but this script amplifies the divides that occasionally creep in between them. For one, the gaping divide between Julie and her mother is explored in greater and more detail, with the mother getting much more dialogue in the script to diagnose Julie’s troubles. And Abbie’s tension with her mother gets another scene as well, where Abbie lies to her about her ability to get pregnant and gets chastised by the mother for her troubles. But the most dramatic tensions occur between the main characters, especially as the film enters its home stretch. In the film, they certainly drift apart, but here that drifting is exacerbated by more active fighting and separation. This starts, as it does in the film, with the scene where, after Jamie uses feminist literature to misinterpret her, Dorothea tells Abbie that she’s not comfortable with giving him that literature. But here, she’s telling this to both Abbie and Julie, alienating both of them in the process whereas she only falls out with Abbie in the film. Then that’s followed by Dorothea seeming to fall out with William, with her realizing “she doesn’t get him at all” and him realizing “he’s tired of feeling judged by her”. And so the subsequent dinner party scene unfolds with added bitterness all around, the tensions overtaking the riotous comedy of the scene (even the hilarity of William spoiling the end of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is immediately followed by him being hurt that Dorothea acts so cold to him), especially with an added scene where Jamie learns that Dorothea doesn’t want Abbie and Julie “raising” him anymore and freaks out at her. Plus, there’s an extended period of time where Jamie doesn’t want to see Julie anymore, instead of the dinner party leading right into them deciding to go up the coast together like it does in the film, and added business with the threat of Abbie having to leave the house. They all seem so much angrier at each other that this section feels like Mills took the idea of a third-act fallout too far for what was a pleasant hangout movie before that. The finished film has just enough conflict to give it a recognizable third act and just a small enough amount of conflict not to cause whiplash from the good vibes of the first two-thirds, while the script makes too sharp a turn into the third act. In the words of Blank Check, this part of the script in particular sees Mills putting too much paprika on the sandwich.

And then there’s the most depressing element of the film proper, the knowledge of Dorothea’s death, which is even more strongly conveyed in the script with frequently-described close-ups of smoke, often from her cigarettes, rising into the air, mirroring her own future ascension at the hands of those cigarettes. In the film, there’s only one of those shots, ominously placed over Dorothea describing the initial symptoms of her cancer, but there’s several in the script, including the opening shot, where the smoke is coming from the similarly-dead car. The knowledge of her death existing in the background is tragic enough, seeing it constantly laid out in the foreground just makes the movie a little too heavy for its own good.

Perhaps an apt metaphor for this shift towards the depressing is the beach. In the movie, it’s a place of astonishing beauty, and a place where Dorothea can try to collect herself and her thoughts. In the script, it’s still that, but Julie also takes pains to point out the leftovers from oil spills that are washing up on it. This version of 20th Century Women still seems like a beautiful thing to inhabit, but it’s more open about the tar that’s lurking underneath it.

Assorted Things

There are some other changes/additions to the script that don’t entirely fit the patterns mentioned above that I want to mention here.

- Abbie’s montage is a bit different, not bothering with her reasons to leave Santa Barbara and instead focusing largely on her time in New York. It also gives her a boyfriend, changed to be one of her teachers in the film (in the script, he plays her teacher in a roleplaying game), and adds an incident where someone jacked off on her walls while she was passed out drunk, which:

- Dorothea makes a Jonestown joke while at work. That’s it, really.

- The character of Julian, the nightclub doorman who eventually gets invited to dinner by Dorothea (played in the film by Darrell Britt-Gibson), is expanded here, with him having more of a friendship with Abbie and her letting him “touch my ass” in exchange for letting Jamie enter the club.

- The montage around Jimmy Carter’s “crisis of confidence” speech here contains a mini-montage of Abbie playing various parts while Jamie takes pictures of her; a “gaudy tourist”, “slutty party woman”, and “over-worked single mom”.

- Abbie and Julie get a full scene together of Abbie taking Julie to Planned Parenthood to get on birth control (this follows the menstruation scene, which in the script makes Abbie take a liking to Julie after she publicly shares her sexual experiences), an idea ultimately covered briefly in Julie’s final montage. Too much of the scene is spent with Julie listening to a worker talk about proper birth control procedures, but there’s a pretty affecting moment afterwards of Abbie crumbling because she sees girls in paper dresses, the outfit she worse when she found out about her cancer.

The Ending

There’s a few new scenes in the lead-up to the ending, including the aforementioned one with the maid, as well as one of William and Jamie finally doing something close to bonding, sleeping in the same hotel room and laughing at the same things on TV. This is the culmination of the added focus on both the absent father and William, and while it’s cute enough, it’s not really a pay-off that’s good enough to justify the shift away from the focus on the women in Jamie’s life.

Following that, the end montage mostly proceeds as it does in the film, but with some small but crucial changes. William’s montage gets one glaring change, with the first of the two wives he mentions dying of cancer instead of simply divorcing him. Now, the finished resolution is pretty sad in how it suggests that William will never overcome his hippieish ways of loving and leaving women, but killing off his wife feels a little too cruel for this character and this movie, especially considering the end already has its share of tragic cancer deaths. But Julie’s montage is the most radically changed part, with no mention of her losing contact with her mother and, even bigger, her having a daughter instead of her choosing not to get pregnant. Every change the film makes to this montage is for the better, from the closure we get with the mother to making the overall character resolutions something other than “everybody gets a baby!” (given that the movie deals with differing models of femininity, it makes more sense to have them travel separate paths than reach the same one).

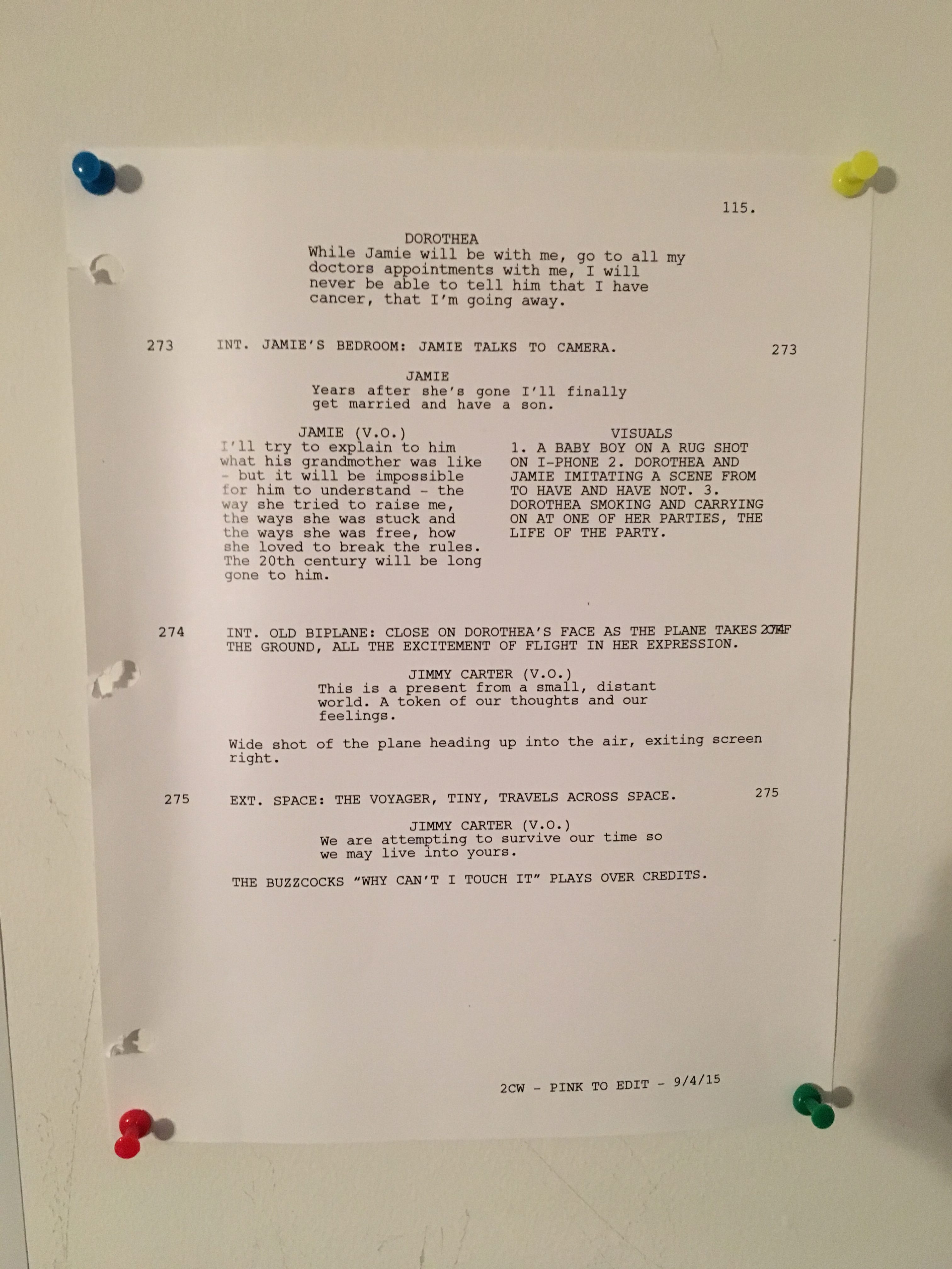

That being said, there is an added moment at the very end that knocked the wind out of me with its beauty. It is transcribed below:

JAMIE (V.O.)

Years after she’s gone I’ll finally get married and have a son. I’ll try to explain to him what his grandmother was like – but it will be impossible for him to understand – the way she tried to raise me, the ways she was stuck and the ways she was free, how she loved to break the rules. The 20th century will be long gone to him.

Now, I see perfectly well why Mills cut this down; the film version cuts everything after the line about any explanations being “impossible”, and the audience gets perfectly well why it would be impossible without the explanations, because of the two hours we’ve spent untangling Dorothea’s various contradictions and grey areas, and also because of the fickle beast that is memory, distorting whatever clear images you ever had of someone. And ending the movie by mentioning “the 20th century” is maybe too close for comfort to “Hey, that’s the name of the movie!” (or the even more dreaded “That’s Chappie”). But goddamnit if reading that and even typing it out didn’t choke me up, because I’m seeing the soul of this beautiful character finally laid bare after living with her for a year. It’s probably best that it’s not in the movie, but I really needed to see it in some form. And I also needed to see the script’s actual final line, from Jimmy Carter’s speech about the Voyager 2:

JIMMY CARTER (V.O.)

We are attempting to survive our time so we may live into yours.

This line is pretty much the only argument I could make in favor of keeping the Voyager 2 thread, because it’s such a powerful summation of the film’s time and place, where people are biding their time in the hopes of something better looming on the horizon (even if so much of what waits for them is only bad news). And it further clarifies how heartbreaking it is that Dorothea died on the cusp on Y2K, being able to see the light at the end of the tunnel but not quite making it there. The 20th century may be long gone to us, but maybe the greater tragedy is that it never ended for her.

The End

20th Century Women is a warm hug of a movie, and it’s been a comfort to me in this last year of almost endless tumult. This script is very obviously the movie that I love, but all the ways that it’s different suggest a movie that I don’t respond to quite as well 0n account of its sadness, one that doesn’t seep into my bloodstream (really, a movie like Beginners, which I love but which doesn’t destroy me and build me back up like Women does). But I’m totally glad I got to experience this version of the movie, both for the tiny moments of sheer beauty in it and for how it shines an even stronger light on the beauty of the finished film. And I’m equally glad you’ve all (hopefully) read along with this and the last piece. Thank you all so much for your time, and stay tuned for a shorter one of these in a week.