Perspective is a funny thing. We all have different ways of approaching just about anything in this world, all stemming from our own personal experiences, and that includes how we approach looking at the past. For many of the people living in bygone era’s we now hold as sacred, there was nothing inherently special about the year they were living in. they were just trying to live out their lives as best they could. The cars we now look at as shining examples of automobile craftsmanship they would just drive around in solely as a means to get from Point A to Point B. The art from these decades we now revere as classics were just the newest movies playing at the multiplex. At the time, what they were going through was just the routine steps of life.

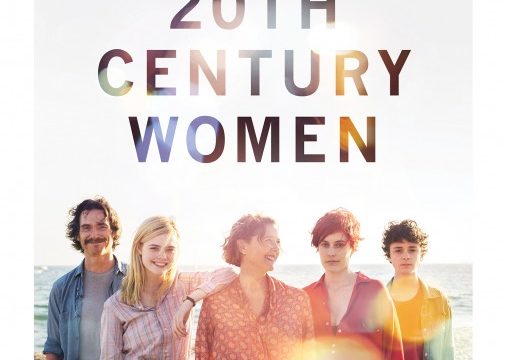

What was mundane and commonplace then has garnered a greater sense of significance both through the nostalgia of people who lived in that era and younger individuals who’ve only seen the 1970’s through pop culture and old family photos. Perspective is funny like that, twisting the ordinary into something greater and that’s the kind of outlook 20th Century Women grabs, runs with and never lets go of. Here we have a simple tale of a cigarette smoking single mom, Dorothea (Annette Bening), who is worried that she’s losing touch with her teenage son, Jamie (Lucas Jade Zumann), whom she feels is becoming more and more rebellious and distant as the days go by.

Dorothea recruits two women living in the same home as herself and her son, rebellious 24-year old Abbie (Greta Gerwig) and Julie (Elle Fanning), to help out her son as he goes through is pivotal teenage years. This means Abbie takes Jamie under her wing while the dynamic between Julie and Jamie becomes strained due to Jamie’s romantic feeling towards Julie. The majority of these events carry narration from all of the various characters in this story, who recount this tale and earlier formative events through narration from their much much older selves. This means 20th Century Women carries a wistful tone to it, as far older versions of the five central characters (there’s also pottery buff William, played by Billy Crudup, factoring into the story) look back on this particular event in touching off-screen narration that proves to be one of the films best central assets.

The tactful use of narration is a brilliant way that Mike Mills screenplay manages to fully immerse the viewer into the varying predicaments facing the lead characters. Through this melancholy-soaked narration coated storytelling, one can get a full perspective on the kind of existences Dorothea, Abbie and Julie live and how the events of this story affect them. All three of these protagonists manage to come alive as different kinds of people, though each sharing the common thread of attempting to chase away the more tragic and lonely parts of their lives through various means and ends. For Dorothea, it’s cigarettes and obsessing over the stock market and her son, for Abbie it’s embracing the punk rock and feminism scene and for Julie it’s rebelling against a home life she doesn’t enjoy by partaking in sex and drugs.

Considering how pervasive the element of tragedy is in this movie, I’m surprised 20th Century Women has been widely considered a comedy, including at this years Golden Globes ceremony (though it wouldn’t be the first time that awards ceremony mistakenly put up a drama for awards designed for comedy/musicals). Honestly, 20th Century Women comes across to me as a more of a quiet tragedy, examining the everyday disappointments and struggles that build up over the years to leave you feeling empty and dejected. Abbie is a prime example of this, a beautifully created character whose various quirks and obsessions feel like they come from an actual human being tormented by the pain of her life going in such unexpected and unwanted directions.

There’s so many scenes of hers where both the writing and the incredible performance form Greta Gerwig just left me a puddle of tears, for a lack of a more analytical description of the emotional power of this character. Gerwig is just so freaking amazing at relaying the inner turmoil Abbie lives with (which stem from her own career troubles and medical difficulties) every moment of every day, whether she’s just walking down the hall, visiting a doctor or engaging in foreplay before sex. To say Gerwig and this script nail this character is an understatement, Abbie is a tremendous feat of a character. A similarly emotionally devastating prowess surrounds the other plotlines driving 20th Century Women as well, and like Abbie, the characters of Dorothea and Julie escape the confines of the one-note archetypes they could have easily become and instead morph into something more layered, more wonderful. Dorothea isn’t just a one-note nagging Mom stereotype, she’s a woman coming to terms with her son and the two very different types of women (Abbie and Julie) she lives with. Julie, meanwhile, isn’t just a hackneyed rebellious teen individual, she’s got her own home life and struggles to deal with that probes deeper into why exactly she is who she is.

The way each of their individual plotlines manage to bounce off each other (like how William’s individual relationships with Dorothea and Abbie come to an impasse) only allows these layered plotlines to grow ever more compelling. And the actors involved all manage to keep right in line with the tone of Mike Mills screenplay, particularly Annette Bening, who works wonders with the subdued morose atmosphere of the film, such as in one bit where her character looks on at a drummer while her more knowledgeable and older narration notes how none of these people can possibly imagine the political, artistic and technological upheavals coming in the decades ahead. That kind of beautiful narration, as well as a recurring visual motif of characters moving around in a sped-up fashion or psychedelic imagery accompanying cars moving down the road, lends 20th Century Women the quality of being visually evocative of someone wistfully recounting memories in their own head.

We’ve all been there when we’re going through the past in our noggins, that experience of looking back on various memories and having them intersect one and another and realizing that days that seemed so inconsequential so long ago reveal themselves to have had a grander sense of purpose when we look at their life as a whole. It’s a beautifully poetic notion, one that the melancholy masterwork 20th Century Women presents in a restrained but all too powerful fashion. Like I said, perspective is a wonderful thing and the one seen in 20th Century Women is absolutely phenomenal to experience.

For fellow Soluter John Bruni’s take on 20th Century Women, please click here