It might be easy to think of 20th Century Women, written and directed by Mike Mills, as a simplistic period piece. The film, however, eludes this categorization, referencing events that make up the collective experience of the past century. The central figure, Dorothea, a divorced single mother in her 50s, grew up during the Great Depression, which has shaped her worldview. She believes in being independent yet creates a household in late-70s Santa Barbara along a more communal living ethic.

The door, then, is always open for Abbie, in her 20s, and William, a handyman whose generation is somewhere between Dorothea’s and Abbie’s. They live at the house, while Julie, a teenager, visits frequently to spend time with Jamie, Dorothea’s teenage son.

Giving rise to the social programs that supported the growth of the middle class, the Great Depression gave promise that national problems could be worked through, a sentiment that lasted through the mid-century. But Watergate and its aftermath pulled strongly in the opposite direction, which ushered in feelings of paranoia and pessimism. This is the mood that permeates the setting: every carefree moment is punctuated by a deeper anxiety.

As a result, the film does not soundtrack the prototypical Southern Californian aesthetic celebrated by Fleetwood Mac and the Eagles. Their songs focused, with varying degrees of cynicism, on the demise of late-60s idealism, but they could only appear, at best, as out of touch with the concerns of Abbie, Julie, and Jamie.

Having lived in New York City until being forced to return to Santa Barbara due to health issues, Abbie is a punk-rock ambassador, bringing with her the music of bands who performed at the venerated club CBGB: Talking Heads, Ramones, Blondie. Meanwhile a hardcore scene is developing in Los Angeles, featuring Germs and Black Flag. Situated a fair drive away from LA, Santa Barbara is getting all of this music by osmosis—through bands influenced by these bands who play at local venues.

Having lived in New York City until being forced to return to Santa Barbara due to health issues, Abbie is a punk-rock ambassador, bringing with her the music of bands who performed at the venerated club CBGB: Talking Heads, Ramones, Blondie. Meanwhile a hardcore scene is developing in Los Angeles, featuring Germs and Black Flag. Situated a fair drive away from LA, Santa Barbara is getting all of this music by osmosis—through bands influenced by these bands who play at local venues.

Therefore, the film does not pursue the route of the failed 2016 TV series, Vinyl, and try to invent encounters between the characters and members of these iconic bands. Instead, owing to Abbie’s interest in photography, we see still photos of punk performers accompanied by pulsing guitar riffs, bass lines, and drumbeats.

Susan Sontag wrote: “As photographs give people an imaginary possession of a past that is unreal, they also help people to take possession of space in which they are insecure.” One of the books Abbie carries with her is Sontag’s book, On Photography. We can see how punk and photography go together, for Abbie. She is insecure for a number of reasons: forced to return home, she is estranged from her mother, left to fend for herself despite her health issues, and feels out of place—especially due to her feminist attitudes that question, and clash with, the more conformist Southern Cal suburban lifestyle.

The film is structured through the complex and changing relationships among Dorothea, Abbie, William, Julie, and Jamie. While the initial premise is that Dorothea enlists Abbie and Julie to help her raise Jamie, these relationships flash forward and back through time and are most certainly not predicated on the usual representations of love and sex. It’s more like being together is what really counts—but the film constantly reminds us that such a relatively simple goal in theory turns out to be quite a struggle in practice.

Trying to get all of this on the screen sounds as if it would be a considerable challenge. Mills makes it look easy. He’s helped a great deal by the actors. Annette Bening, as Dorothea, Greta Gerwig, as Abbie, and Billy Crudup, as William, all turn in performances as if they’ve lived, and are living, inside their characters. It’s not hard to miss the directorial influences here: the emotional improvisation developed by John Cassavetes and the building of character from the ground up that is central to the works of Mike Leigh.

Trying to get all of this on the screen sounds as if it would be a considerable challenge. Mills makes it look easy. He’s helped a great deal by the actors. Annette Bening, as Dorothea, Greta Gerwig, as Abbie, and Billy Crudup, as William, all turn in performances as if they’ve lived, and are living, inside their characters. It’s not hard to miss the directorial influences here: the emotional improvisation developed by John Cassavetes and the building of character from the ground up that is central to the works of Mike Leigh.

The motif of rebellion in suburbia is reminiscent of Leigh’s Abigail’s Party (1977). And like the films of Cassavetes and Leigh, it’s hard to write about 20th Century Women as a narrative with traditional character trajectories based on having problems and solving them. Mills is asking, what’s next after Watergate, which shows us that time-tested methods of solving problems no longer work?

In that way, Dorothea’s strategy for raising Jamie no longer seems like something out of a quirky comedy. Instead, it underlines how subtle conflicts suddenly and unexpectedly flare up. Abbie’s teaching Jamie about feminism, especially when it comes to sex, strikes Dorothea as inappropriate. Their argument reveals much about both women. Abbie believes in telling people how they can lead better lives, even if they don’t understand why. Dorothea believes people shouldn’t be rushed to improve, even if their time runs out.

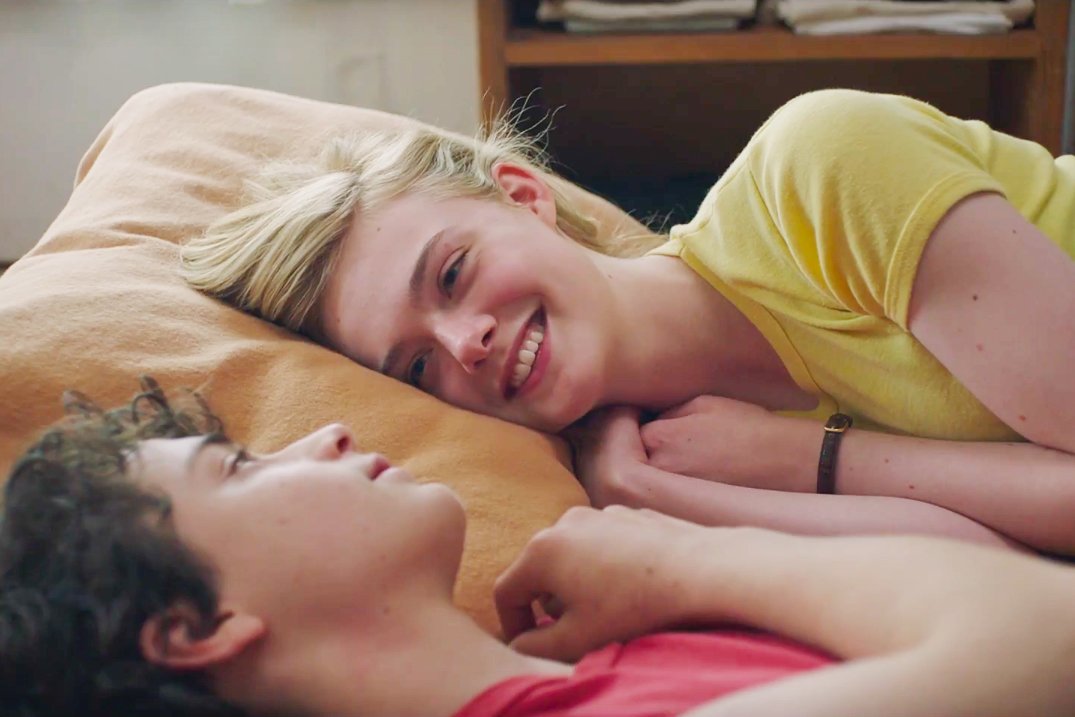

As Julie, Elle Fanning appears to get off to a slower start, but gradually and forcefully shows that she’s realizing how she can manipulate people, and is trying to break this habit inherited from her mother, a therapist. She sees her role in Jamie’s life as a trusted friend, and teaches him a valuable, if difficult, lesson: a person can be both loved and objectified.

As Julie, Elle Fanning appears to get off to a slower start, but gradually and forcefully shows that she’s realizing how she can manipulate people, and is trying to break this habit inherited from her mother, a therapist. She sees her role in Jamie’s life as a trusted friend, and teaches him a valuable, if difficult, lesson: a person can be both loved and objectified.

Needless to say, the film doesn’t objectify any of the characters–they don’t fit into neat categories. The multiple lifelines that intersect and diverge form a panorama, much like the famous time-lapse images of modern civilization in Koyaanisqatsi (1982); this footage is included in 20th Century Women. It perfectly fits with how 20th Century Women translates the idea of life out of balance into a portrait of lives that only in rare moments attain a sense of equilibrium.