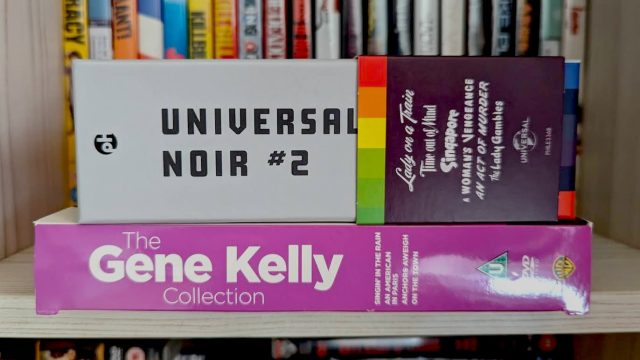

I have far too many unwatched movies on my shelves. Follow me as I attempt to watch all of the ones from the current Year of the Month and figure out what they say about the year in question! Part four launches into 1945, with a double-bill of Anchors Aweigh and Lady on a Train.

Nineteen Forty-Five! A completely insignificant year in world history, when nothing of note happened. Apart from, I suppose, the end of the second World War and the first (and so far, only) time that nuclear weapons were used in combat. Also, half the members of ABBA were born! It’s always fascinating how global warfare does or doesn’t impact the world of entertainment: I keep thinking that such a major conflict is bound to have some noticeable impact on the stories being told, but perhaps it’s more natural that movies should provide an escape? That certainly seems to be the case here, with two extremely upbeat movies that seem designed to let people get away from the horrors of existence for a while. And one of them begins with a murder!

Anchors Aweigh has a military theme, after a fashion, but not in any way that really ties into world news. Gene Kelly and Frank Sinatra play two sailors granted a few days’ shore leave to get into short-lived romantic misadventures and perform a variety of catchy tunes, as was the style at the time — so much so that both the basic premise and both stars would return just a few years later in the better-remembered On the Town. Looking back from 2024, it kinda feels like that film is at least partially responsible for this one being relatively forgotten, but there’s a bunch of fun stuff here that deserves to be remembered.

In this version of the tale, Kelly is — as ever — the confident, charming one, who immediately makes plans to hook up with a lover who has been eagerly awaiting his return. Sinatra is his shy sidekick who needs help getting a date, which feels like it should be a stretch for one of the world’s most famously suave individuals, but somehow it does kinda work: he does a great job being convincingly awkward, and he looks a little goofy in his sailor suit next to Kelly’s athletic physique. Kelly’s attempts to ditch his shipmate for a long weekend of romance are foiled by eight-year-old Dean Stockwell, in his first major appearance: he’s run away from his mother intent on joining the navy, and the only sensible way to get him to rethink his hasty life choices — at least, by 1940s musical standards — is for a couple of real-life sailors to hang around with him and his single mother until everyone has satisfactorily found romance, returned to school and/or performed a selection of amiable musical numbers.

It’s tough to argue that On the Town doesn’t improve on the formula — it has 50% more sailors, it’s more than half-an-hour shorter and it originated the song “New York, New York,” (not that one, the other one — ed.) which is extremely well-remembered for good reason. But Anchors Aweigh is full of fun ideas and charm, and for a long movie, it’s very well paced. It also slightly predates the era when Gene Kelly would grind his movies to a halt to show off for ten minutes, which is a trait I’ve (clearly) never entirely warmed to, despite the obvious skill on display — he gets solo dances here, but they’re far better integrated into the narrative, and that’s a big plus for me. Also one of his showcase numbers involves a dance with Jerry (of “Tom &” fame) in a fun fantasy sequence as he tells a story to Stockwell’s patriotic classmates! That’s almost worth the price of admission alone.

The plot is solidly predictable, but musicals can get away with that more than most genres as long as the song and dance routines are fun and inventive and the script is witty, and Anchors Aweigh ticked all those boxes for me. I’m not going to say On the Town’s relative longevity isn’t deserved, but I will stick up for this one as an underrated treat that still has plenty to offer.

Lady on a Train is a more unusual proposition. It’s a movie that shows up in film noir lists and (as per my backlog) box sets, but while it does tick a few suitably shadowy boxes, it’s a far more light-hearted affair that cheerfully tramples all over genre lines — other lists that it could realistically show up on include “unusual screwball comedies”, “unheralded Christmas movies” and “secretly a musical?” and, impressively, it does a pretty great job at everything it attempts.

The film opens with Nicki Collins (Deanna Durbin), a confident, wealthy young woman, on a train from San Francisco to New York to visit her aunt. At one point, she looks up from her book and witnesses what appears to be a murder through the window of a neighboring building. On her arrival, she ditches the man sent to escort her safely to her hotel (the wonderful Edward Everett Horton) and heads straight to the police, but with her mystery novel still in hand and a story that sounds more than a little far-fetched, the officer at the desk doesn’t take her seriously. She can only think of one other person who might be up for solving a crime — the author of her mystery novel!

All this setup feels like classic murder-mystery stuff but it seems like Lady on a Train was breaking new ground on at least some of this — the “murder witnessed from public transit” idea would crop up again in Agatha Christie’s 4.50 From Paddington twelve years later and has been a mainstay of the genre ever since, right up to the bestselling novel/extremely average movie The Girl on a Train. But it seems to have started here, with the screenplay from Leslie Charteris (creator of the Saint). It’s extremely fun, spiraling out from that initial crime to take in a family feuding over the dead man’s will, multiple romantic subplots, and several musical numbers.

Durbin is great in the lead, whether she’s pursuing the reluctant mystery novelist, evading her father’s attempts to babysit her around the city, impersonating a nightclub singer or trying to figure out which of her male co-stars is a potential romantic interest and which is a potential suspect. It’s a great ensemble, particularly the murdered man’s two disgraced sons (Ralph Bellamy and Dan Duryea) who both get to play with their established personas a little bit as the mystery unfolds.

There are plenty of surprises to be found, both in the mystery itself and in little character touches like one of the villains always holding a cat (hell yeah, one of the best tropes), Bellamy’s character being disturbingly obsessed with his aunt, or one of the tough-guy henchmen being so moved by Durbin’s singing voice that he can’t carry out his crime. It’s not quite a perfect film — a casually racist comment early on firmly dates it, for one thing — but it’s a real joy how it manages to combine the mystery, romance, comedy and music so effortlessly in a fast-paced 94 minutes.

So what do these two movies tell us about 1945? They seem to share an upbeat escapism, although the low-key patriotism of the navy scenes in Anchor’s Aweigh may hint at a little “support the troops!” propaganda. It feels like there may be a little “eye of the storm” optimism here, with darker entertainment to come once more stories were being told by people who had Seen Some Shit, although of course 1945 does have plenty of bleaker entertainment to ofter (Rome, Open City; Detour; The Lost Week-End; etc.). Today’s two films in particular seem to suggest that people just could not stop singing, whether they were technically in a musical or not, and it also appears to have been a time where you could solve basically any problem — whether it’s a mysterious murder or Frank Sinatra’s lack of game — by simply dashing around the city for a few days.