Maybe you’ve been in a relationship where your partner had to go abroad for a year. If not, you probably know somebody who has. Most proponents of temporarily long-term long-distance separations frequently say that with the new technology, it will almost be like living with your significant other. You can Skype across the world for next to nothing, and stay intimate via cyber sex. You can talk on the phone, text, e-mail, send photos, converse…it’ll be like living at home!

Carlos Marques-Marcet’s cinematic debut closely examines the claims that a relationship will be able to sustain the same intimacy over a long period separation. Sergei is a student who is hoping to become a teacher in Barcelona. Alexandra is a photographer who was chosen for a year-long residency in Los Angeles. We meet Sergei and Alex in a 17-minute single shot of a morning in Barcelona, where they have sex and discuss having a baby, before Alex discovers she was selected for a residency in Los Angeles. This opening shot captures the tactile intimacy and familiarity of the couple as they wake up and perform their routines together. Their harmony is never broken up by the force of the editing.

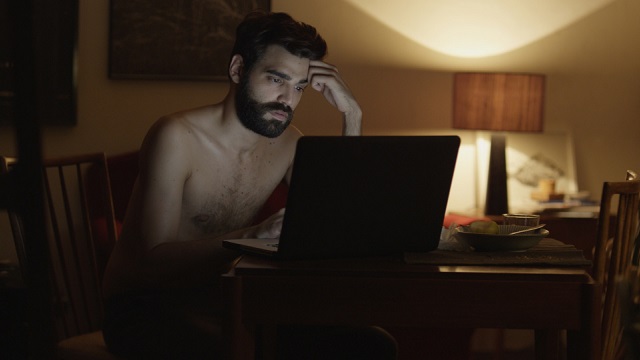

The remaining 90 minutes follows the couple through the interface of internet services. At first, they cling to each other in the face of the new dynamic. Soon enough, they start to discover life outside each other as they change into different, and perhaps incompatible, people than they were as a couple. Sergei and Alex believe that the modern wonders of the world – Phone, Texting, Facebook, Skype – will keep them close to each other, and that their relationship can sustain the long-term absence. Marques-Marcet denotes each subsequent scene with the number of days apart, constantly being aware of the toll that time takes even as technology presents the illusion of closeness.

Tying into the message of technology being illusory, Alex’s project is about the presence of technology in life. She begins by taking photos of hidden antennae in plain sight, such as in elephant statues. Later, she moves on to a more obvious comparison when she films car rides through city streets, and places them side by side with Google Maps going through the same path, hammering home the point that technology brings us the illusion of being connected with the larger world, but this comfort is largely fake.

Sergei and Alex are but mere ciphers for the audience. Marques-Marcet doesn’t put much to their character beyond their history together and their career ambitions. Sergei’s big dominant characteristic is that he’s a Spanish man who has a little bit of a machismo issue, where he dreams that his career is the most important. Alex is a modern woman striving to live her own life and have her own career. Beyond that, we learn little about these characters, and that’s almost the point. Technology has a similar effect on many different relationships, when we can leave the screen and be absent at our leisure. When we can edit and re-edit e-mails instead of speaking from the heart, we lose levels of intimacy we didn’t even know we had.

While 10,000 KM may be working in broader strokes than a movie about a specific relationship, it’s important to realize that it’s not really about this specific couple. Marques-Marcet is more interested in how technology affects us, and how it deceives us. If you let it, 10,000 KM will make you question your own reactions, and you will look at whether their reactions will be similar to your own. Maybe you’ll have a different response. Maybe you’ll be frustrated at one character or the other. 10,000 KM is full of questions and insights that I haven’t seen tackled yet. Original, dramatic, and entertaining, 10,000 KM captures our lives at a crucial juncture of technological innovation.