With the attention that Listen Up Philip has been receiving (review forthcoming), it’s good to remind ourselves that it comes after a film that already displayed Alex Ross Perry’s go-for-broke attitude. Made four years after the supposed end of mumblecore (discussed last week), the film takes up the genre’s challenge to received ways of thinking and feeling, while pointing out the often overlooked cynicism that filmmakers often need to have—the neediness of the characters in films of this genre can reflect on the endless hustle for money to make non-mainstream films. It is, I think, to Perry’s credit that he continues to envision the creative process as a darkly comic act of discovery.

Love, American Style: The Color Wheel

(dir Perry, 2011)

The last brief shot is an open front door: a perfectly apt symbol for how the film keeps everything up in the air. Each scene serves to upend the last, often transitioned through blackouts. In addition to its chaotic worldview, The Color Wheel is comfortable with and well-suited for the economics of small-scale representation—the complexity of family dynamics are carefully explored without showing the parents at all; we understand who they are by watching their children, Colin, played by Perry, and J.R., played by Carlen Altman, the co-writer of the film. J.R. convinces Colin, who still lives at home, to take a road trip with her to Boston, where she is ending a relationship with her former broadcast professor and moving out of his apartment.

With regards to this film, the question of what genre it falls under has two answers. One: it could be seen as using the mumblecore aesthetic to create a very dark and weird story. Two: it could be interpreted as a reaction against the cuteness factor (obviously writ large in the sit-com/rom-com tradition) that mumblecore is often accused of embracing.

That said, The Color Wheel proudly displays the influence of John Cassavetes, who helped to inspire the mumblecore movement, providing in 83 minutes a compressed journey through Cassavetes’s work, from the jagged rhythms, drunken parties, and use of close-ups in his early film Faces (1968) to the transformation of sibling relationships and mystifying final sequence in his last film Love Streams (1984).

But The Color Wheel also has a distinct politics that recalls the razor-sharp alienation projected by early-70s road movies such as Wanda (1970), Five Easy Pieces (1970), and Two Lane Blacktop (1971). Like these films, The Color Wheel features motels and restaurants in towns that are sleepy, if not stagnant, serving to spotlight Colin and J.R’s restlessness. They lack any sense of security, either at home or on the road, which fuels their bristling sarcasm, awkwardness, and penchant for self-sabotage. Colin and J.R. both have the knack for saying the wrong thing at the wrong time; they both can see what’s wrong with each other, but not themselves. Colin accuses J.R. of having no clue about how to realize her dream of becoming a television news anchor. J.R. accuses Colin of having given up his dream of becoming a writer and settling for a job as a corporate drone.

But The Color Wheel also has a distinct politics that recalls the razor-sharp alienation projected by early-70s road movies such as Wanda (1970), Five Easy Pieces (1970), and Two Lane Blacktop (1971). Like these films, The Color Wheel features motels and restaurants in towns that are sleepy, if not stagnant, serving to spotlight Colin and J.R’s restlessness. They lack any sense of security, either at home or on the road, which fuels their bristling sarcasm, awkwardness, and penchant for self-sabotage. Colin and J.R. both have the knack for saying the wrong thing at the wrong time; they both can see what’s wrong with each other, but not themselves. Colin accuses J.R. of having no clue about how to realize her dream of becoming a television news anchor. J.R. accuses Colin of having given up his dream of becoming a writer and settling for a job as a corporate drone.

Their arguing is interrupted by passages of silence during the car trip, giving the sense of motion without any escape from feelings of loneliness and futility. This is not some sort of hipster ennui, because we get the impression that neither character remotely knows how to act cool (or if they do they’re not interested in doing so).

But that does not mean they’re not into improvising in any given situation. Although the script was fully written, there are exhilarating moments when both Perry and Altman explore a range of acting styles (sometimes deliberately awkward or bad) to investigate what their characters are capable of doing. For example, check out Colin’s completely awful attempt to talk his disinterested girlfriend into having sex before the trip.

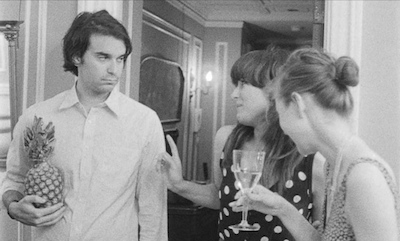

The film is built around two brilliant set-pieces that, like in Cassavetes’s films, run unexpectedly long. In the first, J.R. confronts Neil, her professor. Tension builds from the start when J.R. and Colin arrive at Neil’s apartment and meet a young woman who has taken J.R.’s place. Already dismayed, J.R. becomes more angry as Neil attempts, while doing little to conceal his contempt, to act out a farewell scene with her. As Colin hovers in the background, J.R. reads Neil the riot act for his failure to assist her in gaining job contacts, while Neil continuously reminds J.R. of her immaturity, a charge undercut by his constantly petulant tone. J.R.’s ferocity in this scene reveals a passion that is decidedly non-ironic. Neil comes across as blatantly irresponsible for having used his professional standing to seduce her, and then throwing her aside once his interest has subsided.

If J.R.’s confronting Neil is a sardonic write-off of authority—further splintering generational connections, the second major episode takes the familiar setting of an unpleasant party scene and pushes it in an unusual direction. J.R. runs into two former friends, who tell her that an entertainment agent they know will be at their party, and convince her to attend. J.R., not suspecting that the invite is a set-up (a frequent Cassavetes motif), convinces Colin to come with her by telling him that one of her friends, on whom Colin had a childhood crush, will be there. But the plan to humiliate J.R. at the party is ineffectual, for not only does J.R., again, not have a clue; everyone else is too eager to talk about themselves, bragging about their minor accomplishments, and revealing themselves to be completely pathetic in J.R.’s eyes. By the time everyone seems to remember the plan, drunkenness has resulted in their losing motivation to carry it out.

Strangely enough, Colin takes center stage in this scene. After being bullied by two guys, who resent his being at the party, he eventually finds his former crush and takes her aside. They start making out with escalating passion, only to be interrupted by J.R.’s entrance. While surprised, Colin seems all too willing to quickly bring the amorous encounter to a close (an astute viewer will wonder why). As Colin and J.R. leave the party still in full swing, her two former friends muster the courage to badmouth her to her face. Despite the trying night, Colin sticks up for his sister.

Strangely enough, Colin takes center stage in this scene. After being bullied by two guys, who resent his being at the party, he eventually finds his former crush and takes her aside. They start making out with escalating passion, only to be interrupted by J.R.’s entrance. While surprised, Colin seems all too willing to quickly bring the amorous encounter to a close (an astute viewer will wonder why). As Colin and J.R. leave the party still in full swing, her two former friends muster the courage to badmouth her to her face. Despite the trying night, Colin sticks up for his sister.

It is rather safe to say that the ending comes as a surprise. The idea that, finally, Colin and J.R. are made for each other is pushed to the taboo-breaking point. Of course, few expressed much concern when Jack White of the White Stripes used to pass off his wife, Meg, as his sister: it did have a certain studied theatricality, owing to the traditions of blues music. But in The Color Wheel this deliberate confusion makes for a much more transgressive scene that just goes to show what the fantasy of being who you want to be can really mean when it means being like someone else—a fascinating perspective on a personality in crisis.